Theft in the Xbox Scene - Part 1

Introduction

This is not an article I want to be writing. It is not something I ever imagined I would have to write. But to explain why I am writing it now, I need to provide some history.

Corrections and Updates

Corrections and updates for this post can be found here.

Backstory

My journey with the original Xbox began about six years ago, inspired by the HDMI mods I had seen for systems like the Dreamcast and N64. Growing up, I didn’t have much. A Game Boy Color, an N64, and eventually an Xbox were the only consoles I ever owned as a kid. But it was the Xbox that stuck with me the most.

Years later, I wanted to relive that experience. I wanted to sit down and enjoy some of my favorite games again, like Fatal Frame 2 and Conker’s Bad Fur Day, but on modern hardware with a cleaner signal. That curiosity led me to explore what it would take to bring HDMI to the original Xbox.

I’ve always had a deep interest in reverse engineering. As a kid, cheat devices and emulators fascinated me. They became a kind of escape from a life that, at times, felt like it had very few constants. Around the age of ten, I discovered the memory editor on the N64 GameShark. That discovery lit a fire. I wanted to understand more, so I learned programming and started writing my own tools. Eventually, that replaced the pen-and-paper notes I had scribbled down as a child.

When I lost my father figure not long after, programming filled that void. It gave me purpose, focus, and a sense of control at a time when everything else felt unstable.

Developing the XboxHDMI brought all of that back. The joy of discovery. The thrill of building something new. And along the way, I met people who became real friends. <3

Midwest Gaming Classic 2025

When I finally launched XboxHDMI, I had no idea what to expect. I figured it might be a fun side project. Something I would work on during weekends and maybe sell a few kits here and there. Once I recovered the initial costs, I planned to open source it.

But the launch went far beyond anything I could have imagined. Orders came in fast. Maybe it was the $60 price tag, maybe it was the timing, or maybe the Xbox still meant something to a lot of other people too.

Then COVID hit. Supply chains dried up. Shipping delays frustrated everyone. It was a hard time for many of us. But we pushed through. We kept going.

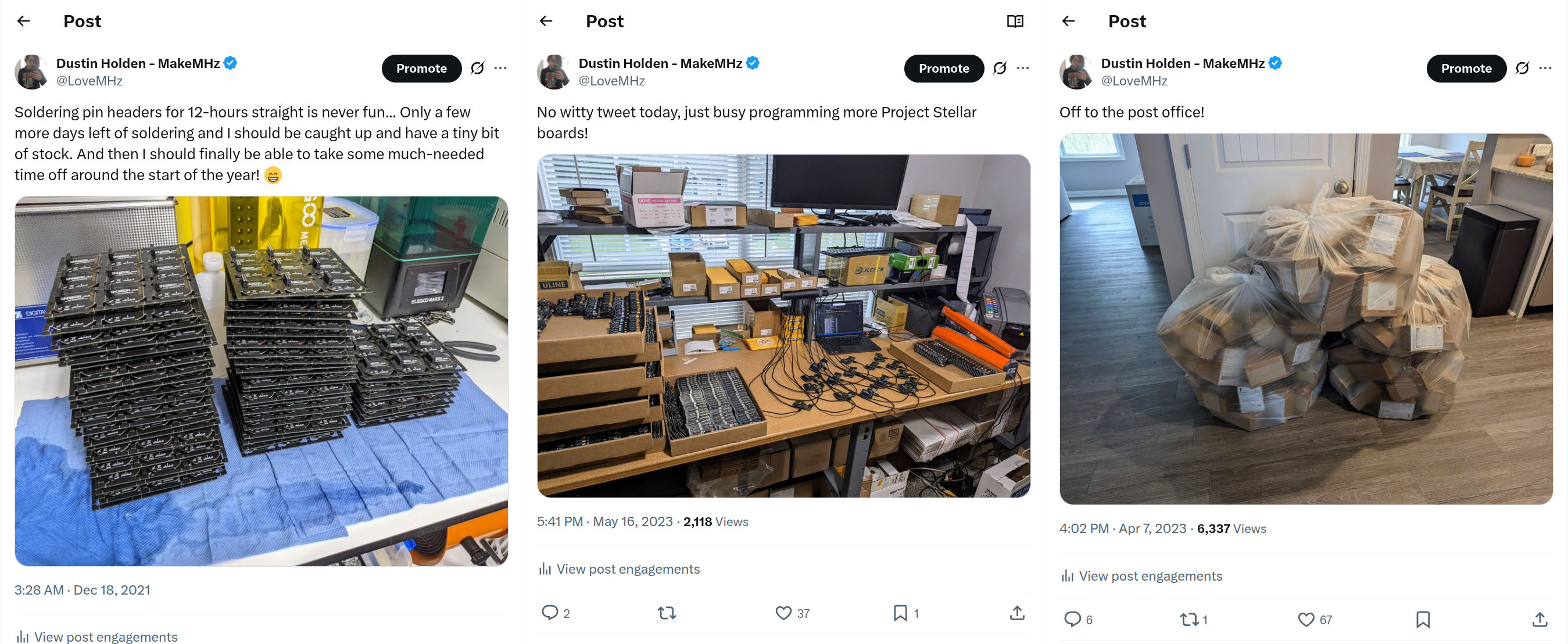

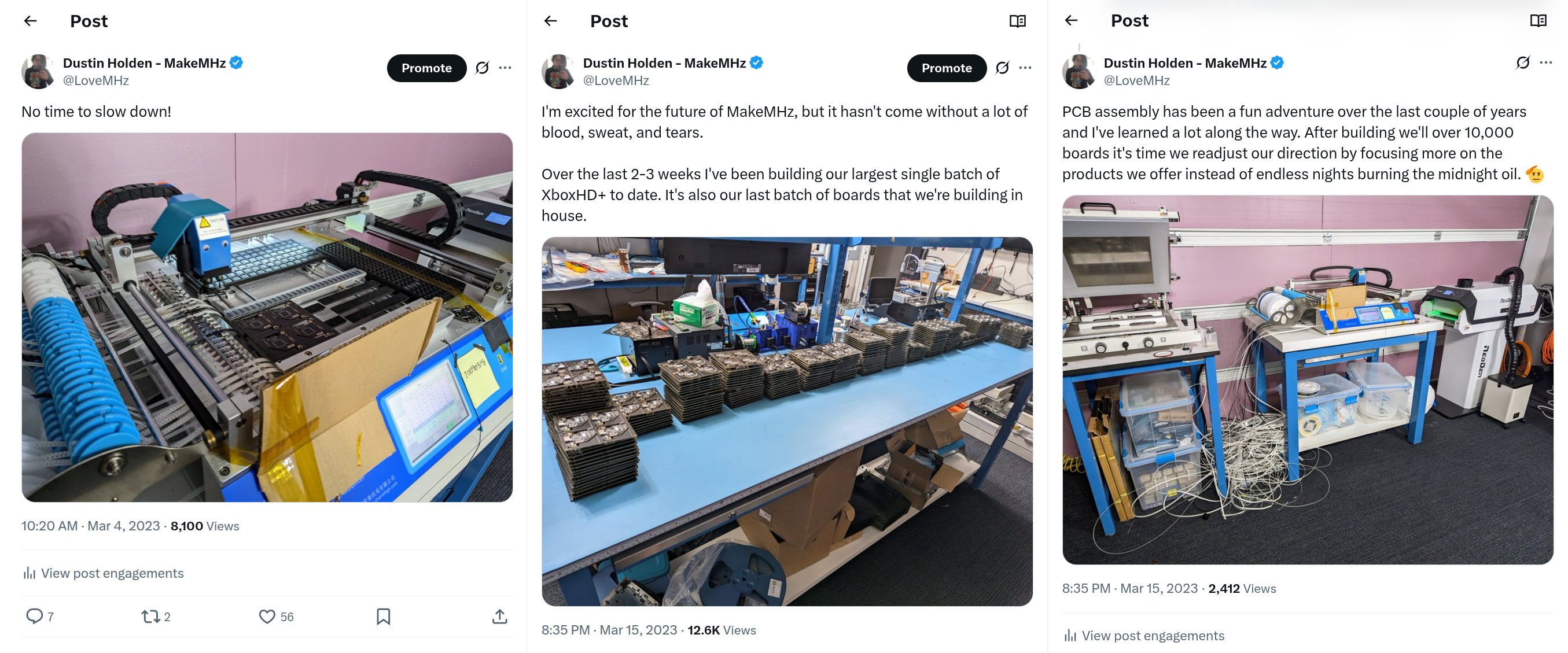

But I quit my job anyway to do this full time. It wasn’t an easy choice. I gave up a steady paycheck, time off, health insurance, and stability. I had saved enough from my day job to take the risk, and I believed in what I was building. I even had enough to fabricate the boards myself and handle everything from design to fulfillment on my own.

I wish I could say it’s been easy, or even always fulfilling, but it hasn’t. Anyone who works with me knows how much I put into this. I work non-stop, and I mean that in the most programmer sense possible. I’ve taken just a few days off a year. I answer support messages on holidays. I chip away at documentation and development deep into the night.

I wouldn’t trade it. Even when I look back on one of the worst medical experiences I’ve had, I try not to think about how differently things might have gone if I had kept my job with insurance.

I do wish I had more time with family and friends. But they understand. They know what this work means to me. This isn’t just about hardware. It’s about preservation. It’s about making something that lasts.

Project Stellar launched at the end of 2022. It was another passion project I couldn’t let go of. All the research from XboxHD+ felt like it had more to give. I wanted to keep fixing, keep improving, and keep exploring. I knew from the beginning it wouldn’t be highly profitable. It’s a more expensive product and the audience is smaller. But I had faith that the Xbox and retro gaming community would support it.

And I have to say, recreating an operating system from scratch, legally and cleanly, has not been easy. But it has been rewarding. Spending weeks to fix a single edge case in a game that has been broken for a decade is the kind of work I live for. I couldn’t imagine doing anything else.

All of that makes what I am writing now so much harder.

Because while we were focused on building something meaningful, others were quietly copying, stealing, and taking credit

for work that was not theirs.

This article exists because this cannot continue.

Why Now?

When I first got involved in the Xbox community, I was pretty outspoken about theft and the general disregard for intellectual property. There are plenty of old screenshots floating around of some of my hot takes, and while I could have worded things better, I still stand by the core message. I believe we can all do better.

I’ve tried speaking out before. But every time I did, it led to personal attacks against me and against my company.

Accusations like this are not just misleading. They are part of a larger pattern used to discredit and silence anyone who pushes back against theft. This is one of the reasons I stayed quiet for so long.

I’ve stayed quiet for years to avoid the drama and protect the work we were doing.

I’m writing this now because that silence has only made things worse. It is time for things to change.

The Xbox community is better than this. This is the same community that built projects like the open-source NKPatcher, long before I came along. It proved that legally extending the retail Xbox kernel was not just possible, but practical. Projects like nxdk have gone even further by showing that legal, independent toolchain development can work and thrive.

I’m also writing this now because I’m tired. I’m tired of constantly worrying that everything I’m working on is going to be stolen the moment it is released. This is not how things should work. It’s not fair to my mental health. It’s not fair that updates to Stellar are delayed so we can implement obfuscation and anti-circumvention measures, just to slow down the people trying to take our work.

I’m writing this for the thousands of people who have put their trust in our work. We are just weeks away from reaching 10,000 orders shipped, not including retail partners. All of those people are being stolen from too, whether they realize it or not.

And I’m writing this for future developers. Even those who may one day replace what I’ve built. If the community accepts theft as normal, then there is no real path forward for anyone who wants to build something original. It becomes impossible to compete with shortcuts, and that drives real progress out of the scene.

What Needs To Change?

-

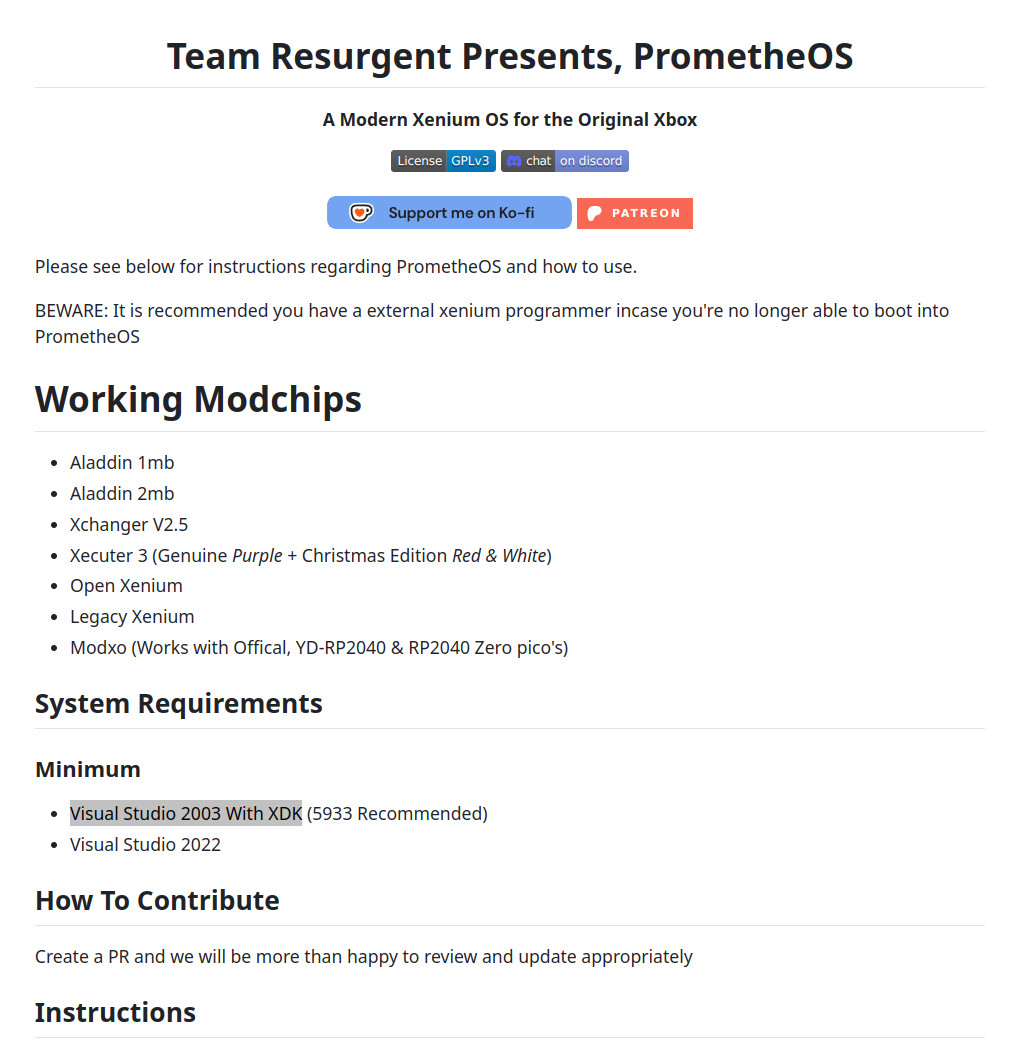

Stop misleading users into thinking Modxo, PrometheOS, and CERBIOS are open source. Modxo was once open source but now uses a restrictive license (non FOSS). 1 2 PrometheOS is not an operating system; it is an Xbox application built using a stolen SDK and a stolen BIOS. CERBIOS is closed source and built on leaked kernel code along with stolen work from others. 1 2 3 4 5

-

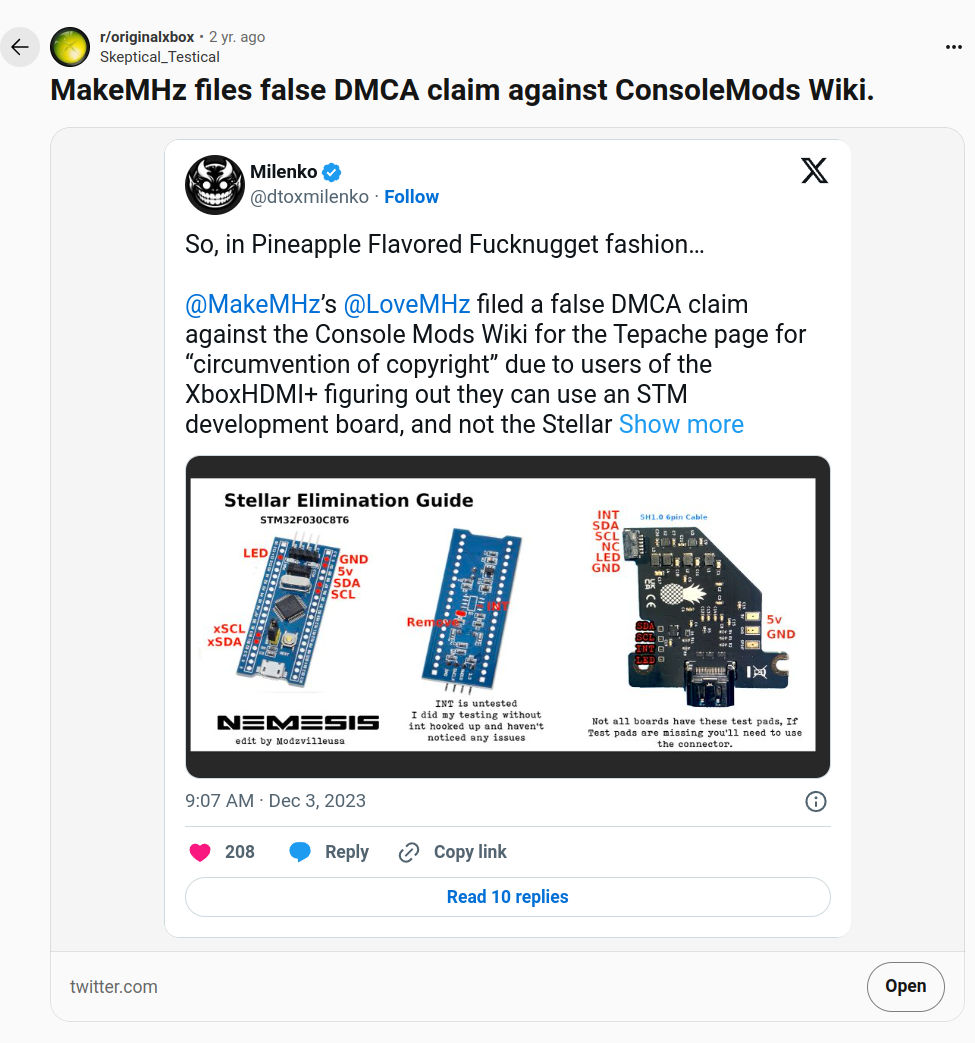

Stop encouraging theft of the XboxHD+ and Legacy kit by telling customers to “just find the firmware.” 1

-

Developers should stop claiming they are not stealing while at the same time publishing guides that explain how to do exactly that. 1 2

-

Stop using alternate accounts to fish for implementation details or gain access to private work. 1

-

Stop making up claims that Stellar is anti-community, including false accusations like “Stellar intentionally broke support for XCAT.” The truth is that XCAT’s own DRM prevents it from working. Nothing was done on our end to block it. 1

-

Stop making claims that we have abandoned the XboxHD+ Legacy kit. This is the first time since the original XboxHDMI launch that the legacy, no-modchip option, has been truly out of stock. We are actively working on it. Recent trade-related issues, including tariffs, have caused unexpected delays. 1 2

This is only a small part of the harassment, theft, and misinformation we have dealt with.

Who?

Cerbios / Team Resurgent

I’m calling out Cerbios / Team Resurgent. This includes all of its members: EqUiNoX, HoRnEyDvL, Hazeno, and Dempsey_86.

These individuals have repeatedly shown a disregard for intellectual property, copyright, and the work of others. Their actions are not isolated incidents. They are part of a long-running pattern of theft.

Moderators of r/originalxbox

I’m calling out the moderators of the Original Xbox subreddit: Derf_Jagged, TXCrunchBite, OGXboxGamer, GoTeamScotch, AlbinoSheepDawg, KeepForgettingLogin, awesomesprime, Random_Shadowscale, DivideByZer0, and ulubulu.

These moderators continue to allow harassment, misinformation campaigns, and the promotion of stolen work. Some have even gone as far as promoting it directly. 1 2

Xbox Scene Discord

I’m calling out the Xbox Scene Discord for hosting and supporting ongoing theft of our work.

Others

I’m calling out darkonecustoms.com and ogxstore.com (Andr0) for selling products that rely on stolen work from the XboxHD+ project. 1 2 3

XboxHD+

Summary

To understand how the theft of XboxHD+ occurred, we need to take a step back and explain how this project began. Some of this has been shared before, but given the ongoing efforts to copy and clone our work, I want to be cautious while still providing enough detail to show how we got here.

The XboxHD+ project originally started as XboxHDMI in late 2019 or early 2020. During early development, we discovered that we could either build an expensive FPGA-based solution or implement extensive software patches. We chose software, in part because an FPGA would not fully resolve every video-related issue on the Xbox. That decision led to one of the largest software projects I have ever worked on, though I did not realize it at the time.

The initial idea was simple: patch the last retail Xbox BIOS, which supported all hardware revisions, with just enough logic to pass AV initialization and GPU configuration data to a microcontroller on the XboxHDMI. This approach worked well at first. It allowed us to inject handwritten assembly into the existing kernel with minimal disruption, which was important because there were only a few hundred free bytes available to work with. Anything more complex would have been nearly impossible in that environment.

We briefly explored porting the patches to other BIOSes, including iND BIOS, but this quickly turned into a nightmare. After significant effort, I discovered that the iND BIOS had been compiled from leaked source code and was heavily hacked together. At this time CERBIOS did not exist.

As a result, over a year’s worth of research and patching logic no longer applied. We abandoned any further attempts to port the patches and focused on building something more sustainable.

In April 2021, we rebranded XboxHDMI as XboxHD+ and launched firmware version 2.0.0. The new name was meant to reflect that it provided “HD plus more.”

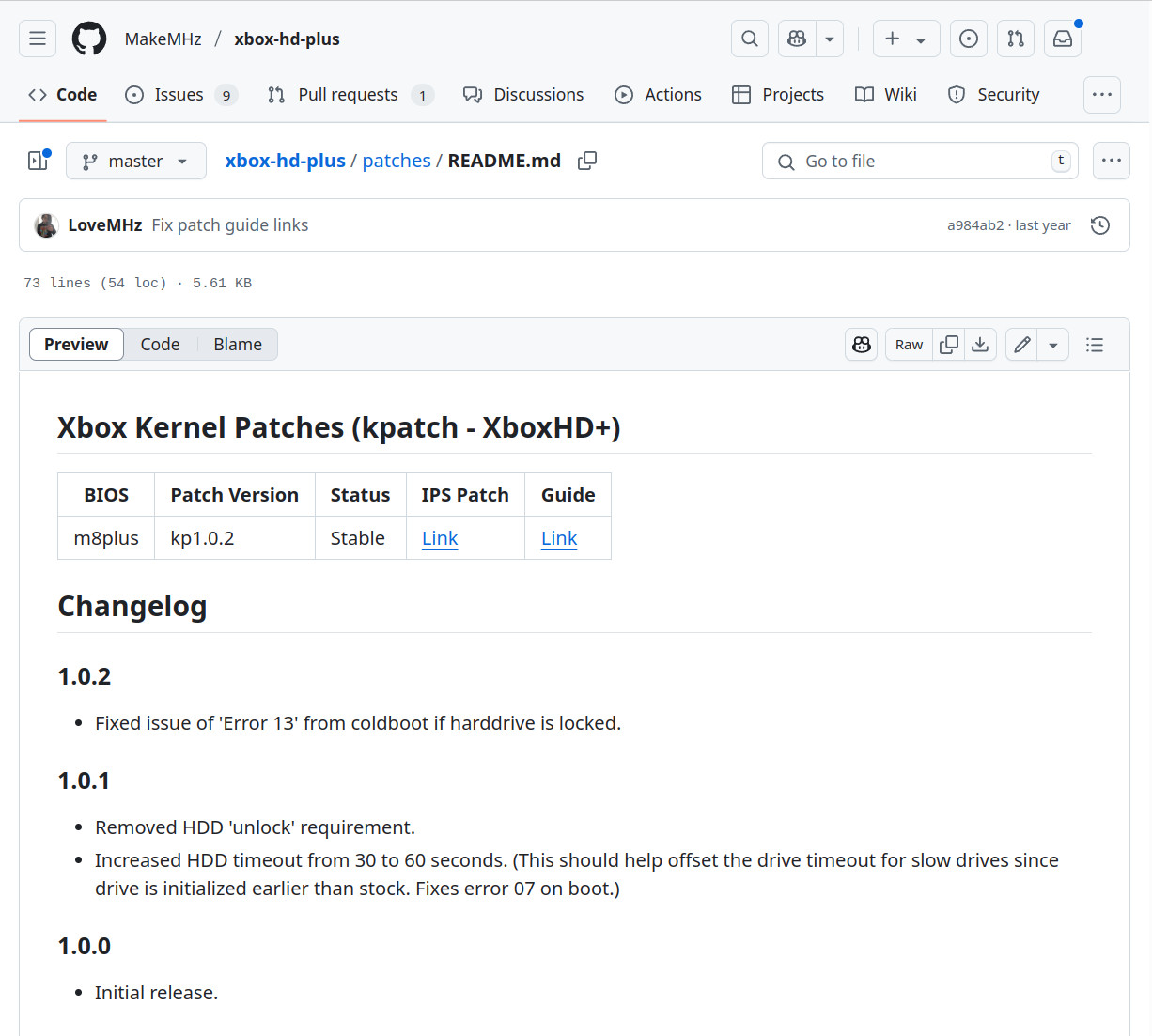

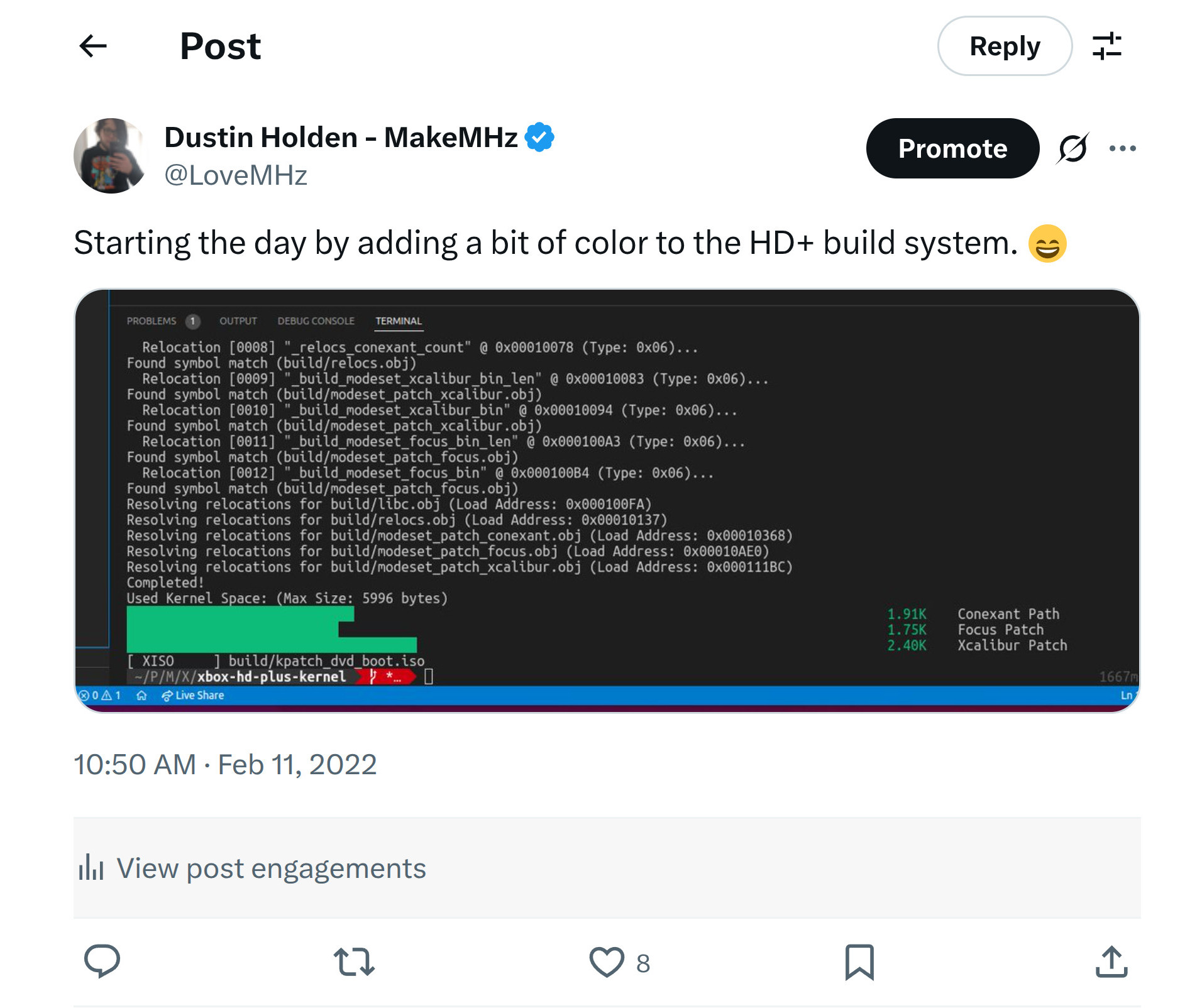

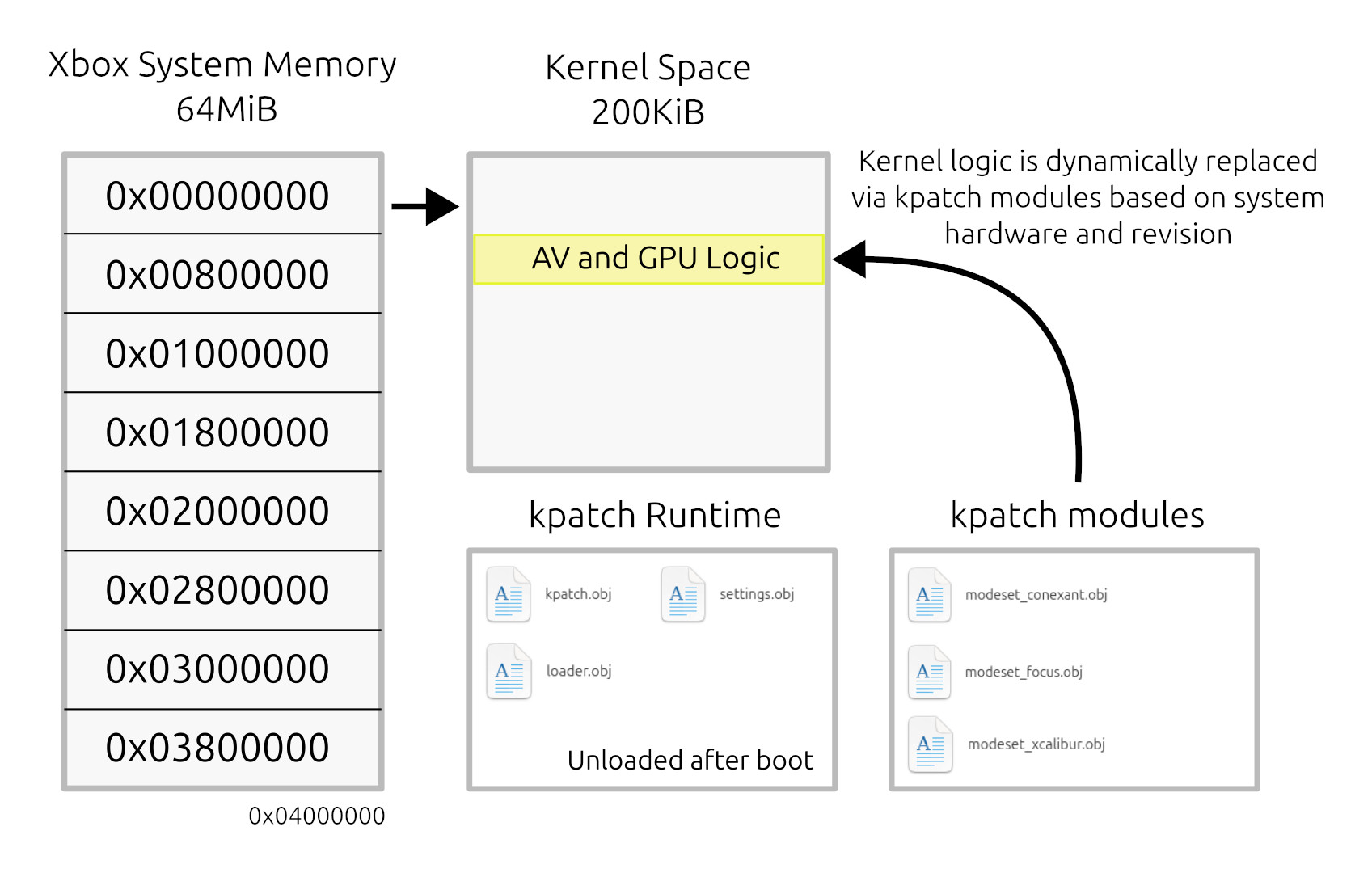

At this point, we moved away from manually patching the kernel on every update and introduced a system I developed

called kpatch. This was a minimal loader that ran at boot and executed what we called the XboxHD+ runtime. We made

kpatch open source to make it easier to integrate, and it became the foundation for future development.

The runtime would detect which Xbox revision it was running on and load the appropriate module. Each module was written in C and compiled specifically for that hardware revision. This let us replace hardware-specific kernel functions with reimplemented versions optimized for each system. It also gave us more space to work with, since we could target unused or replaceable code in a structured way.

This architecture made it possible to fix longstanding issues and improve video output beyond what the original Xbox ever supported. We added upscaling, better widescreen handling, and even per-game fixes. Because the runtime could be updated separately from the BIOS, users could upgrade features just by replacing a file. The kpatch build system and the XboxHD+ runtime became the foundation for what would eventually evolve into Project Stellar.

This design was intentional. It allowed for modular development, future porting to other BIOSes, and easy updates for users. But that is not the path CERBIOS chose.

Instead of using or building a system like kpatch, CERBIOS appears to have copied the XboxHD+ runtime logic directly

into its kernel. This was not an integration. It was a transplant.

As we will highlight throughout this article, the design decisions made by the CERBIOS team do not reflect original development. The methodologies appear to be copied directly from the XboxHD+ runtime, which is copyrighted and not public.

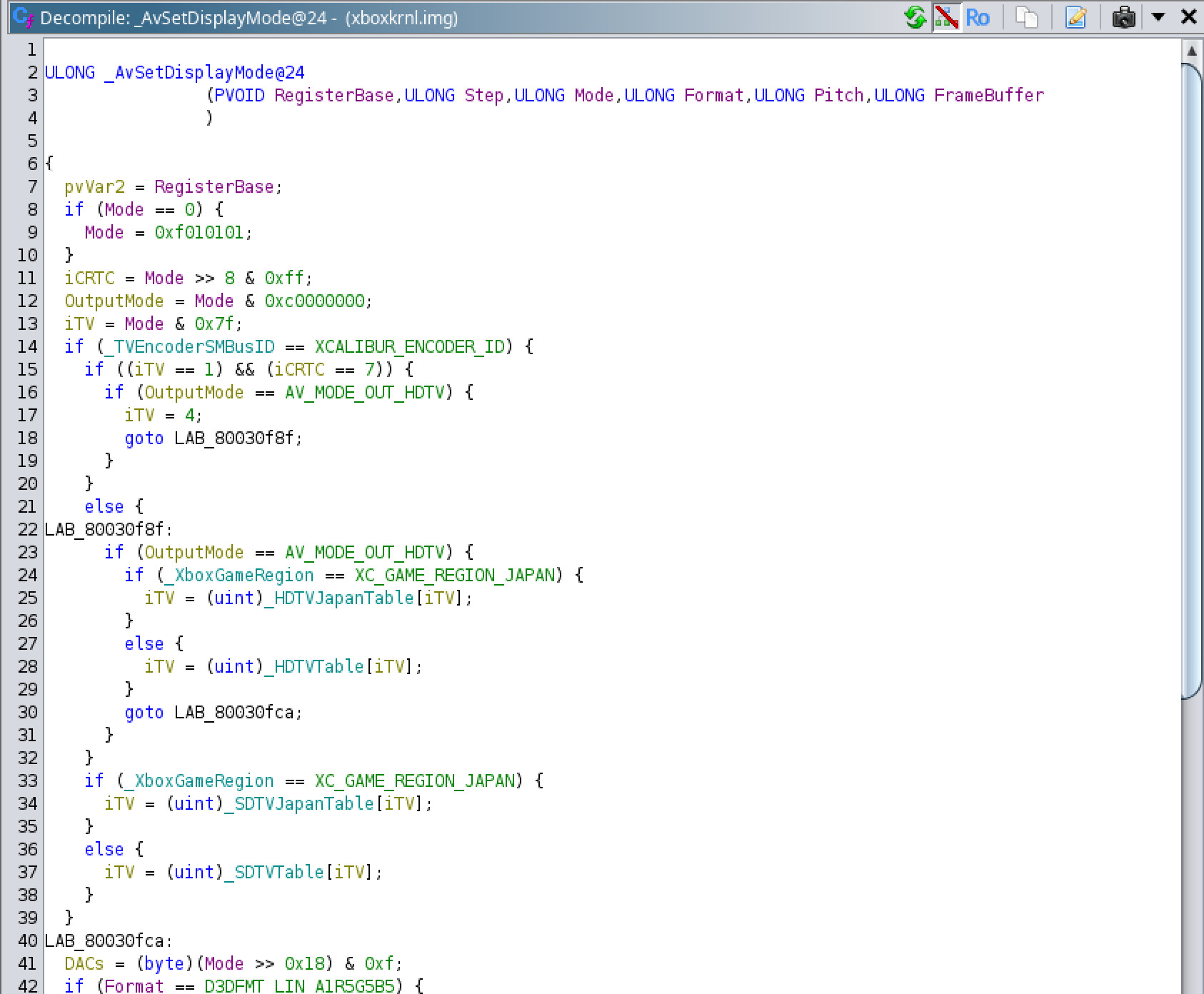

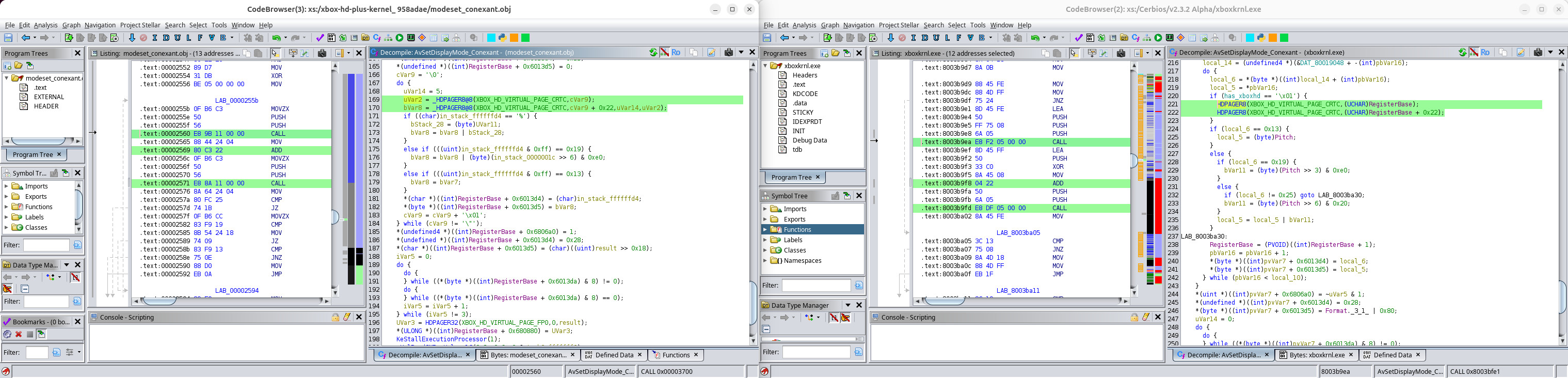

The first red flag is their handling of the function AvSetDisplayMode. This is a relatively straightforward kernel export

responsible for setting up the GPU and video encoder based on the selected video mode. On the original Xbox, most of this

work is done using lookup tables, with minor conditional logic based on the encoder type. Under XboxHD+, these lookups are

redirected to the microcontroller.

CERBIOS takes a very unusual approach. They re-implemented AvSetDisplayMode three separate times, once for each encoder.

This makes no practical sense. It triples the code size, increases complexity, and does not follow the design of the

original kernel. More importantly, it closely mirrors the XboxHD+ runtime structure, where we split modules by hardware

revision to reduce memory usage. That design made sense in a boot-loaded runtime. It makes no sense inside a BIOS kernel

unless it was copied directly.

Anyone reverse engineering the Xbox video subsystem would have seen that a single function with conditional logic is the right approach. Duplicating the logic three times is not only inefficient but also suggests that it was taken from a system designed to be loaded dynamically at runtime, not built directly into a BIOS. That kind of structure only makes sense when you have the flexibility and memory overhead that a separate runtime allows. This matters because the Xbox kernel has strict size limits. Without additional memory, like what Project Stellar provides, pushing memory usage higher introduces uncertainty. It increases the risk that existing software will behave unpredictably or fail entirely.

That is not all.

Other parts of the project have also been copied. Code that was released under the GPL for the XboxHD+ application has shown up in PrometheOS as well. This includes struct definitions that only exist in our released source code and cannot be reconstructed by reverse engineering. These structures have been copied almost verbatim, with only minor changes such as capitalization. This is not reverse engineering. This is copy and paste. And it is a clear violation of the license and theft of our work.

The Important Questions

-

If CERBIOS truly developed their work independently, why does their code mirror the structure of the XboxHD+ runtime, which was never publicly released?

-

Why would anyone re-implement AvSetDisplayMode three separate times, when conditional logic in a single function is the clear and correct solution?

-

How did struct definitions from our GPL-released userland application end up in PrometheOS, when those definitions cannot be recovered through reverse engineering?

-

Why are memory usage patterns and hardware handling strategies identical to ours, even down to function placement?

-

Why would a BIOS be written in a way that pushes it closer to unknown memory limits, unless the design was copied from a system intended to run as a boot-loaded runtime?

Theft in Plain Sight

The comparisons in this section focus exclusively on code and behavior that were never part of the original public domain release of the XboxHDMI patch. The early patch I released was minimal, designed only to initialize video output and hand off control. It does not include subroutines for the virtual SMBus tables, configuration, or initialization.

What follows are similarities that exist only in the private, copyrighted runtime and cannot be explained as reimplementations of public work. These are not isolated coincidences. When viewed all together, I believe they show a clear pattern of copying.

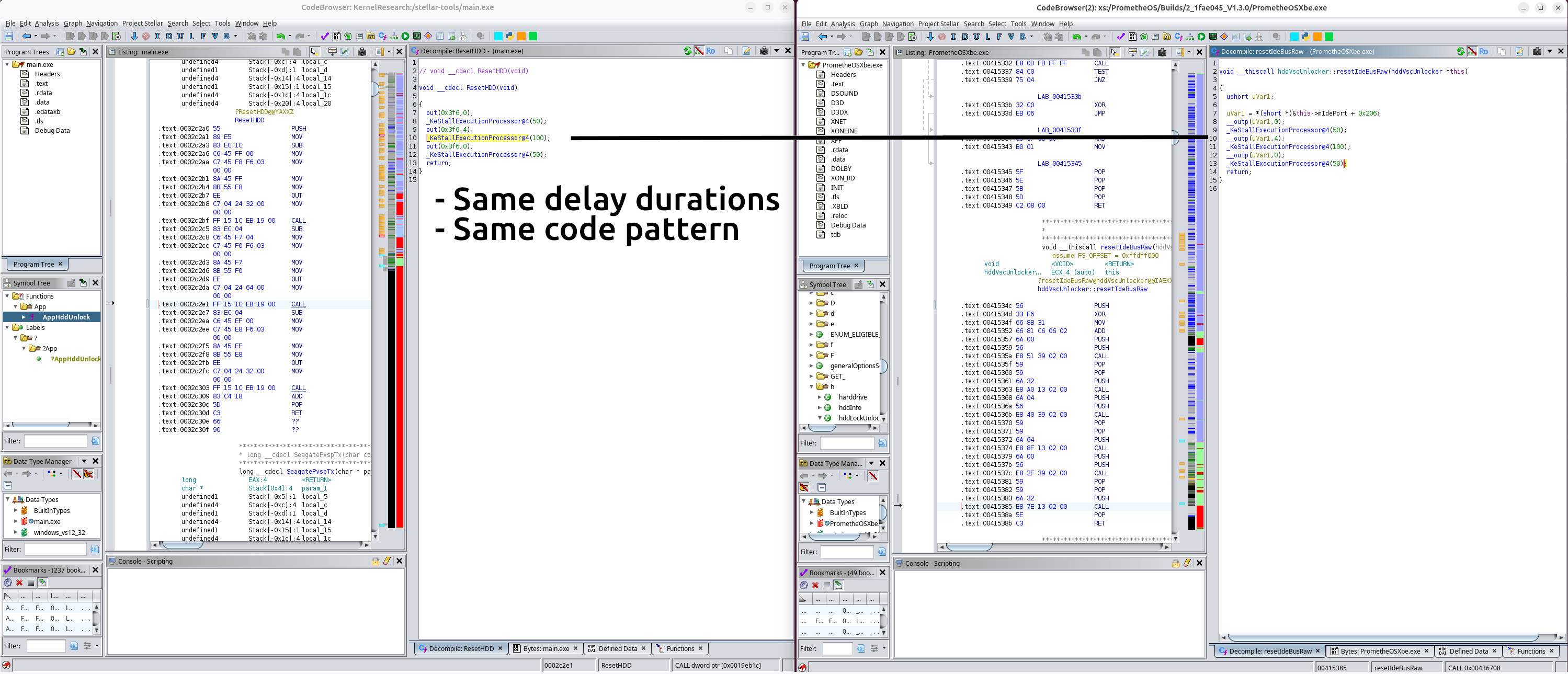

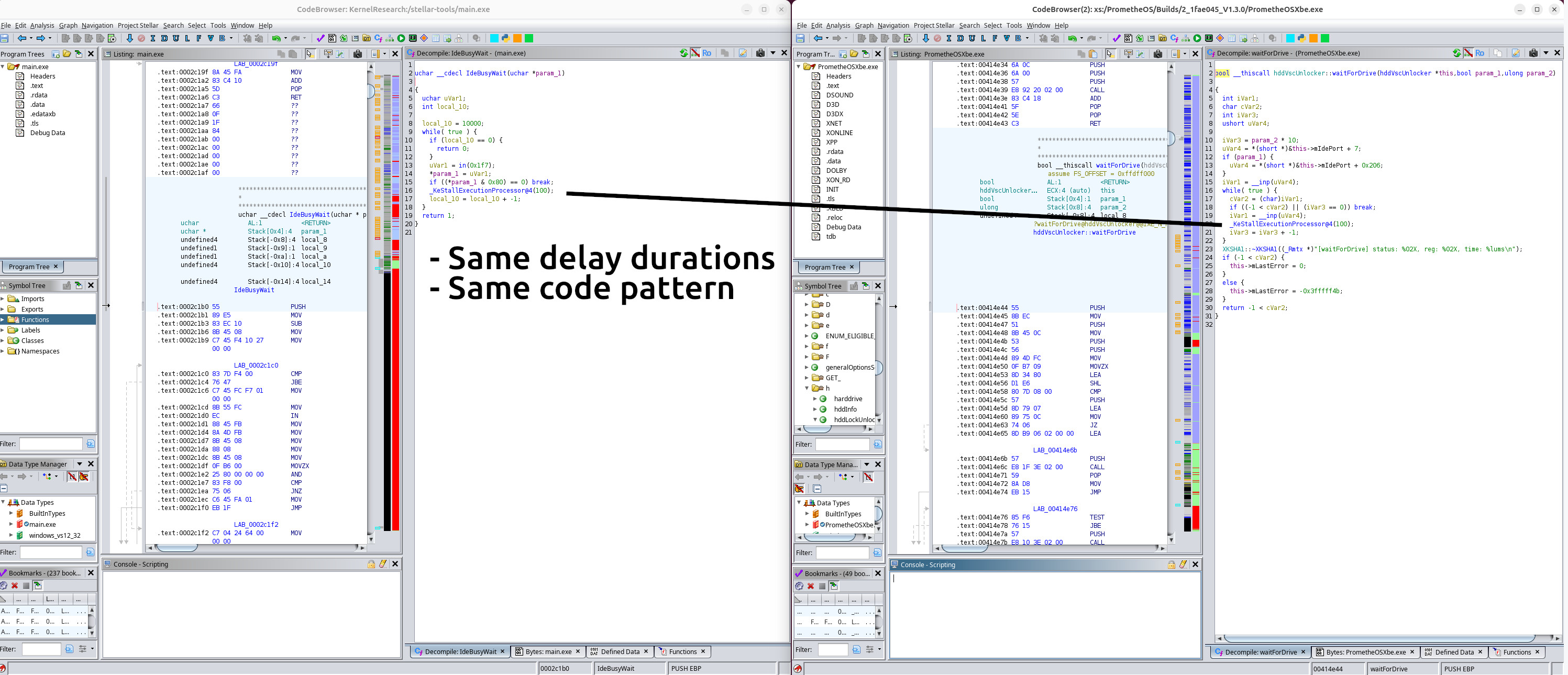

The same logic of applying the exact same delay after storing the video mode.

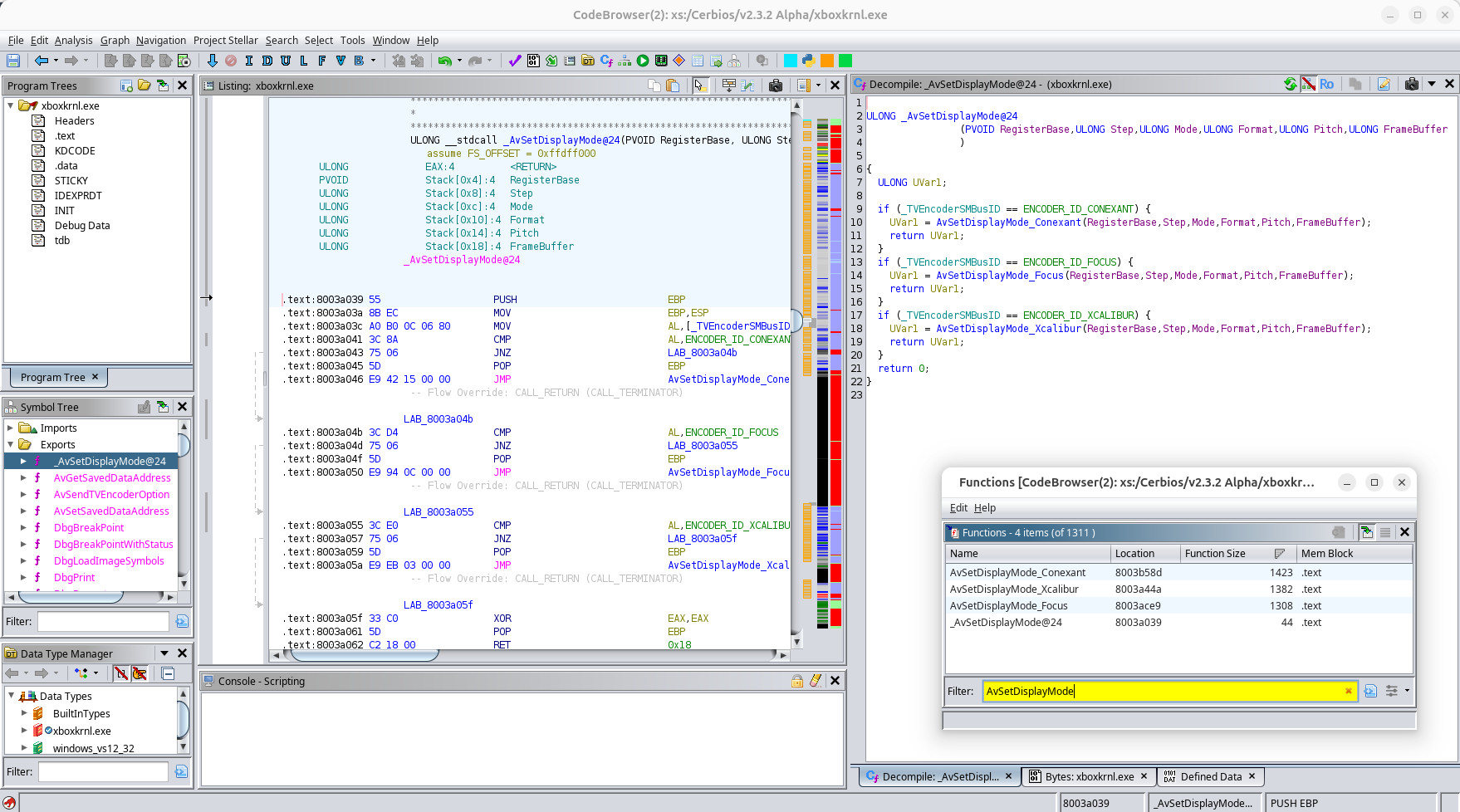

As part of the XboxHD+ runtime, I introduced a small helper routine for setting the current virtual page. Functionally, it’s extremely simple as it’s just a single register write with a hardcoded offset. It duplicates logic that already exists elsewhere in the runtime, and looking back, even I’ll admit it should have just called the standard register write function.

There was no technical reason to split it out. It was a quick decision made during development, and it remained because it worked.

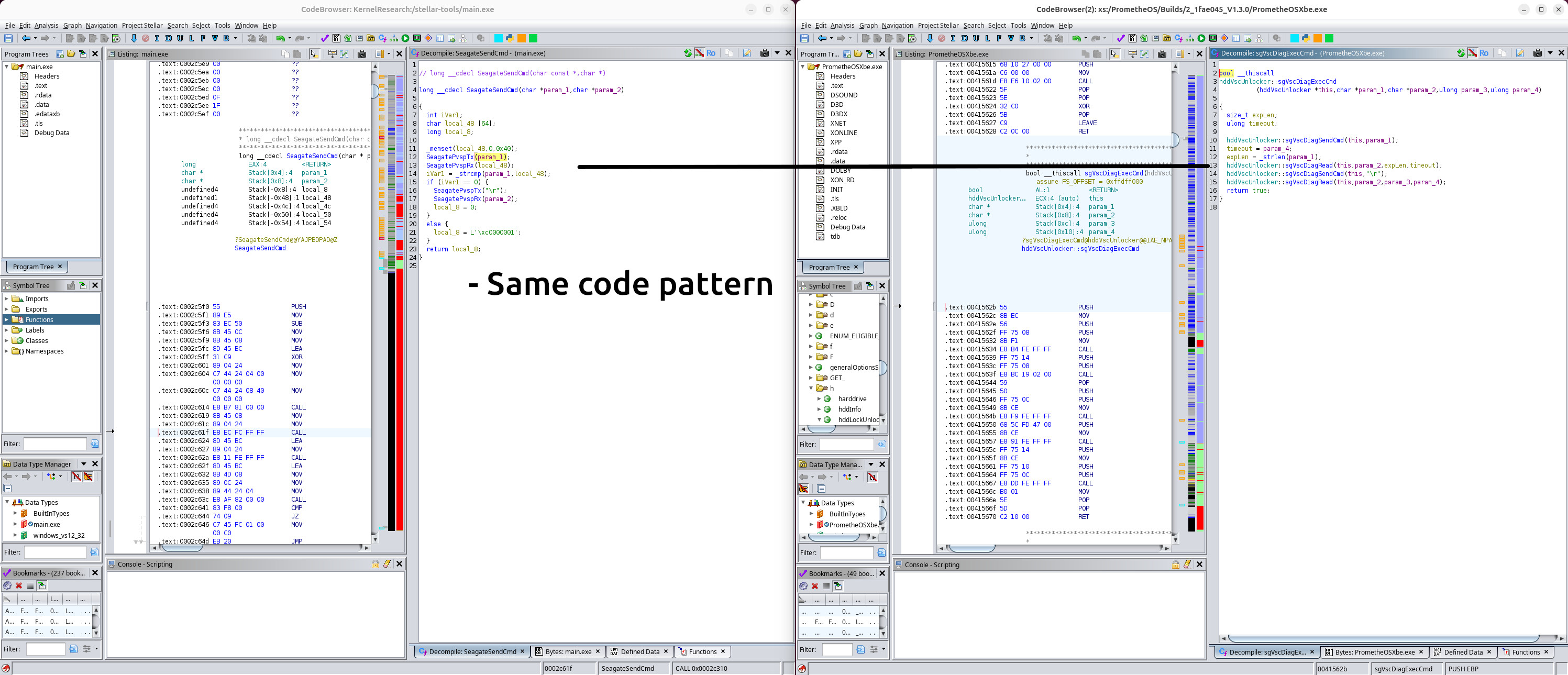

The screenshots below show that CERBIOS includes the exact same kind of helper routine, with the same structure and purpose. This is not a common design pattern. Anyone writing this from scratch would have just used the existing write register subroutine. The fact that this unnecessary and oddly specific function appears in both runtimes is not a coincidence. I believe it is another clear example of copied code.

Identical virtual page setter routine found in both XboxHD+ and CERBIOS. The logic duplicates existing write functionality that I believe would not have been independently re-created without copying.

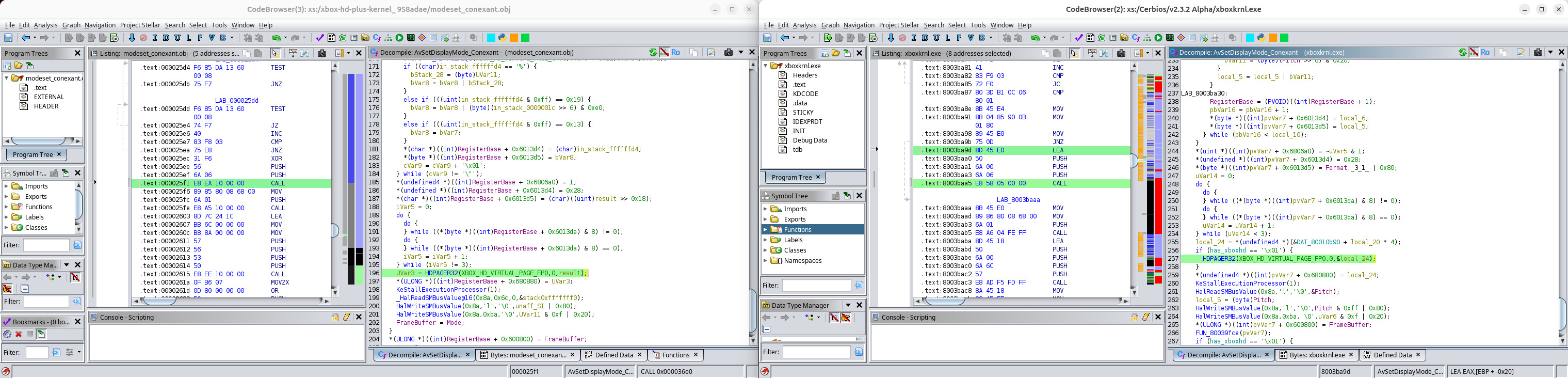

Another example appears during the XboxHD+ initialization sequence. In early XboxHDMI firmware, we encountered a bug where, in I2C software mode, the microcontroller could overflow before it entered hardware mode. To resolve this, we added a very specific delay and call pattern in the initialization logic of the XboxHD+ runtime. This fix ensured reliable behavior under edge conditions caused by queued SMBus transactions in the Xbox kernel.

This delay is subtle and internal. It would not be visible externally, because SMBus operations are abstracted and queued within the Xbox kernel. There is no way to observe or infer this behavior by watching from the outside.

Yet, somehow, CERBIOS includes the exact same logic. The same call structure. The same delay in the same place. The only difference is that CERBIOS omits this delay in unrelated areas, which further highlights how deliberate its inclusion is here.

CERBIOS initialization includes a delay and call structure identical to XboxHD+, originally added to fix a microcontroller overflow issue in I2C software mode. This behavior is not externally observable and would not appear without access to the XboxHD+ implementation.

The next example is not just a design copy. It’s a direct copy of source code.

The screenshot below shows the PrometheOS source code defining a settings struct that matches our own, almost line for line. This struct was published as part of the open source XboxHD+ application under the GPLv2. But in PrometheOS, it has been taken without attribution, and more importantly, used in a way that is not compatible with our license. This is not just a license violation. It is source-level theft.

What makes this even more telling is that they copied struct members that are not implemented in their own code and could not be reverse engineered. These fields serve no purpose under the XboxHD+ runtime or in PrometheOS but appear exactly as they do in our code, with the same names and the same unused placeholders. That cannot happen by coincidence.

PrometheOS struct copied directly from GPLv2 XboxHD+ source code, including unused and unimplemented fields that cannot be reverse engineered. No attribution. No license compliance. This is source-level theft.

Where Does the Theft End?

Since the release of XboxHDMI, there has been a consistent effort within parts of the Xbox scene to clone, copy, and steal whatever they can. This is not new. It has been happening in the open for years.

At least four separate projects have attempted to recreate or reverse engineer XboxHDMI or XboxHD+, not through original development but by following, dissecting, and imitating our work as closely as possible. With CERBIOS and PrometheOS, the line between inspiration and theft is not blurry. It no longer exists.

Even now, it is difficult to find a major project in this space that is not either directly benefiting from CERBIOS’s stolen work or openly working to copy and replicate what we have built. What started as quiet imitation has become a public ecosystem centered around copying. And somehow, this behavior continues to be rewarded and normalized.

There are clone devices already on the market. Sellers advertise them and tell buyers they “just need to find the firmware”. These are not throwaway comments. Members of Team Resurgent have previously written guides on how to bypass our copyright protections in the past, and those same techniques are now being used to install stolen firmware onto unauthorized hardware.

This is not about gatekeeping. It is about respecting the time, effort, and work that go into creating something new. The theft is not some distant danger; it is already happening behind closed doors. Stolen work is being rebranded, repackaged, and quietly sold back to the very community it was taken from.

HDD Unlocking

Summary

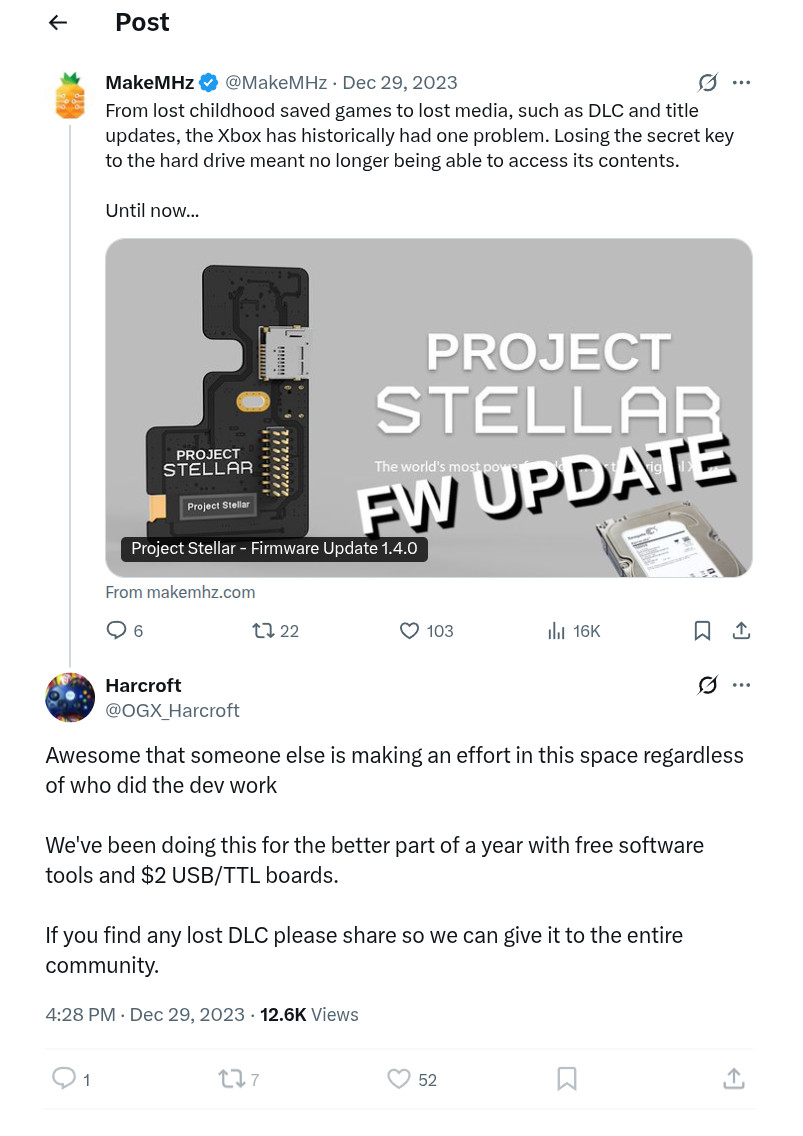

On December 29, 2023, we released firmware version 1.4.0 for Project Stellar. This update introduced, for the first time, fully integrated support for unlocking original Xbox hard drives directly from a running system. This feature had been in development for over a year.

Our work was based on in-depth reverse engineering of original Xbox hard drive firmware. To our knowledge, outside of private commercial data recovery tools targeting specific models, there were no known public methods for unlocking these drives. No documentation existed that demonstrated how to apply these techniques in the context of the Xbox, and no prior tool supported all drive variants over IDE from a running system.

Even more significant, this was an entirely new side channel attack that allowed drive unlocking to be performed directly over the IDE bus.

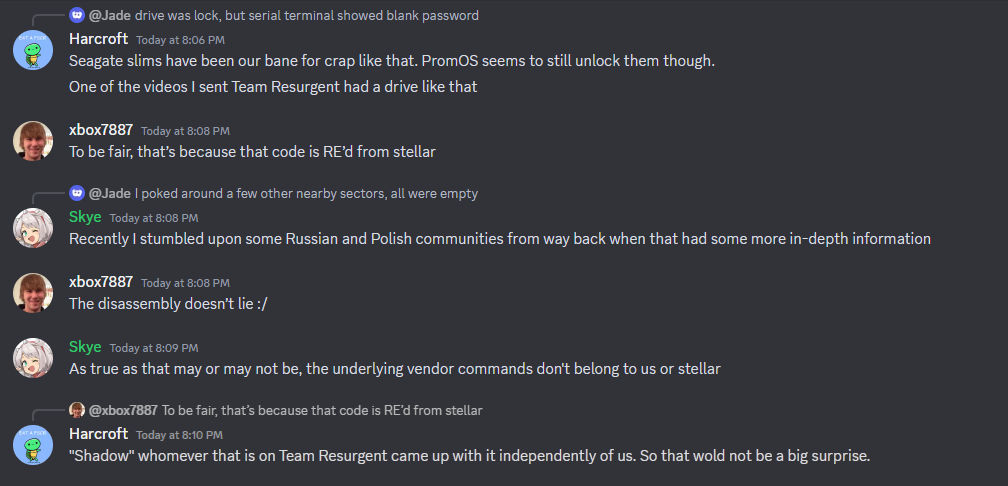

Later that same day, Harcroft, a member of the Xbox Data Preservation Discord and other related projects, publicly replied to our announcement, stating:

We've been doing this for the better part of a year with free software tools and $2 USB/TTL boards.

The implication was clear: that this was old news, that what we had built was nothing new, and that the feature had already been available in the scene for some time.

The Important Questions

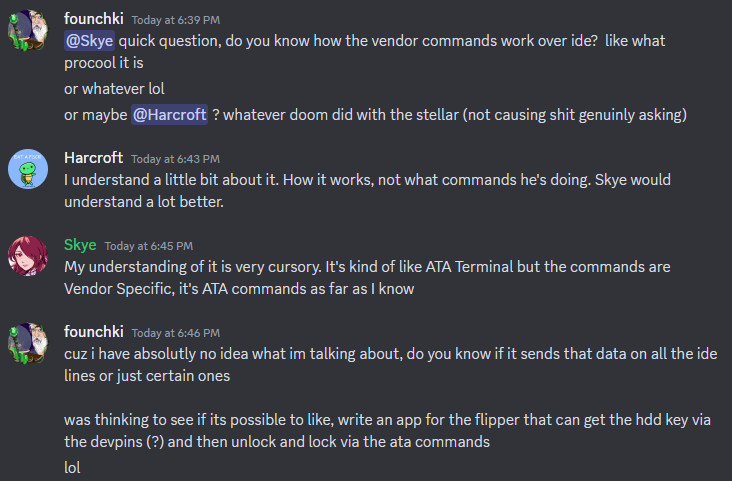

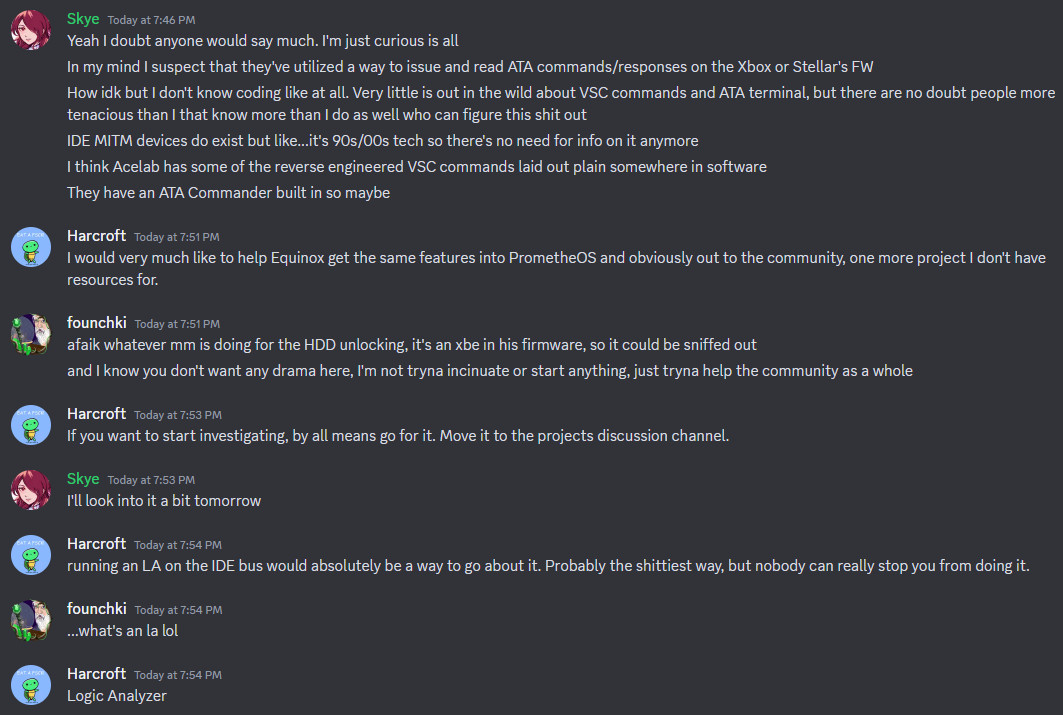

- If this had already been done before, why does no one now seem to understand how Stellar works?

Public Chat on Jan. 8th 2024 - Xbox Data Preservation Discord

- If you’re not reverse engineering Project Stellar, how would you know that the unlocking logic was moved to a separate XBE?

Public Chat on Jan. 8th 2024 - Xbox Data Preservation Discord

-

If this is your own original implementation, why does the code match our patterns and not yours? Ours was originally written for the Stellar kernel, which lacks a full runtime library and was only moved to an XBE at the last minute. Your version uses direct kernel calls instead of the common RTL functions found throughout the rest of your codebase, which are provided by the stolen XDK environment.

-

How is it that the temporary sleep and delay values that we implemented, down to the microsecond, also appear in your code?

-

Why was the source code for the first release of PrometheOS with this feature never released? Seems odd for an “open source” project.

GitHub

- Who is this mysterious “Phantom” member that joined the team? They haven’t been seen since… Scapegoat?

Public Chat on March 1st 2024 - Xbox Data Preservation Discord

Theft in Plain Sight

In this section, we’ll present direct comparisons between disassembled code from Project Stellar and PrometheOS, showing unmistakable similarities that go far beyond coincidence. Screenshots and annotated listings will follow to allow anyone to verify the claims for themselves.

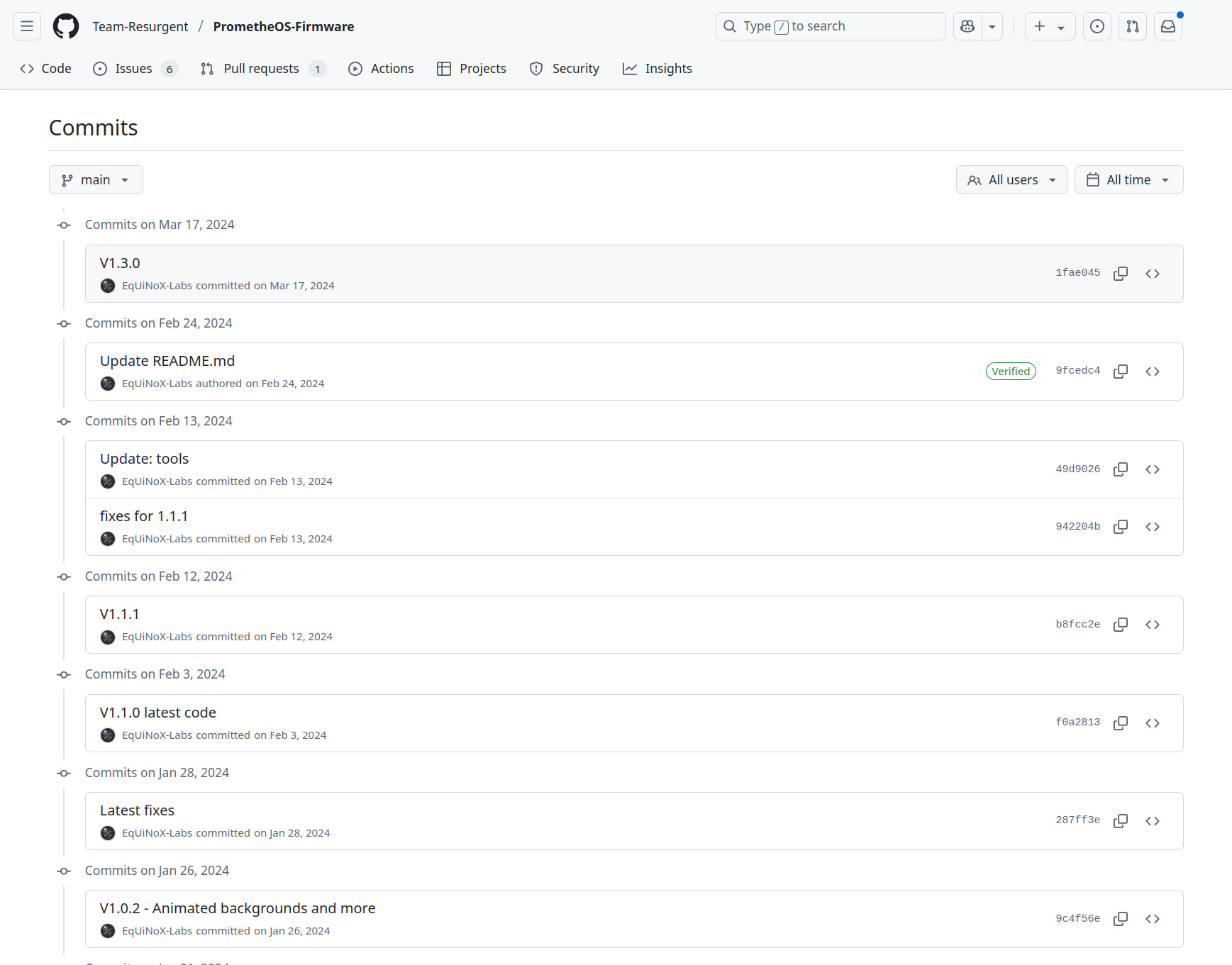

On February 25, 2024, nearly two months after Stellar’s 1.4.0 firmware release, Team Resurgent published PrometheOS v1.2.0. [1] This version introduced a new feature: support for unlocking original Xbox hard drives.

We’ll start with the smoking gun.

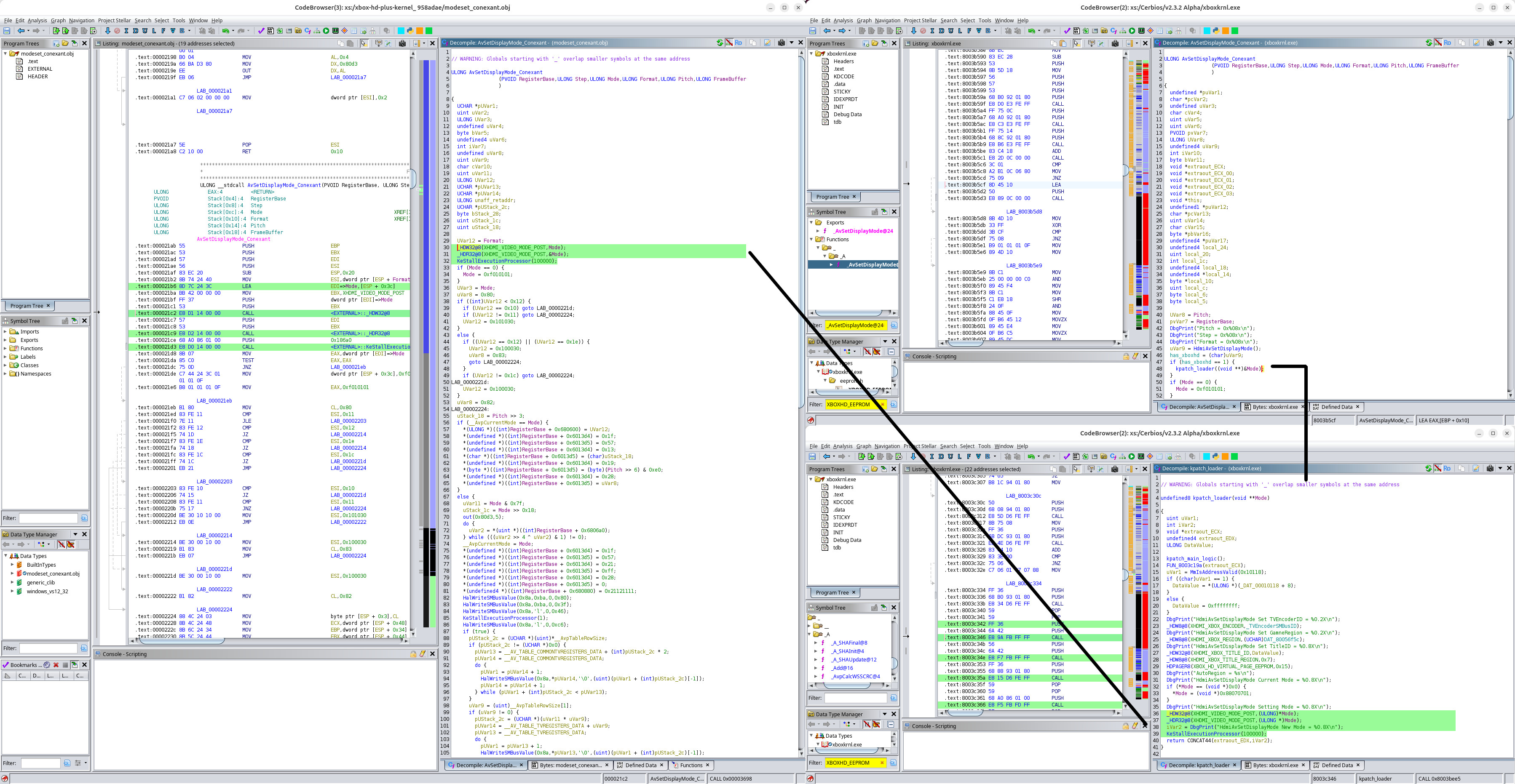

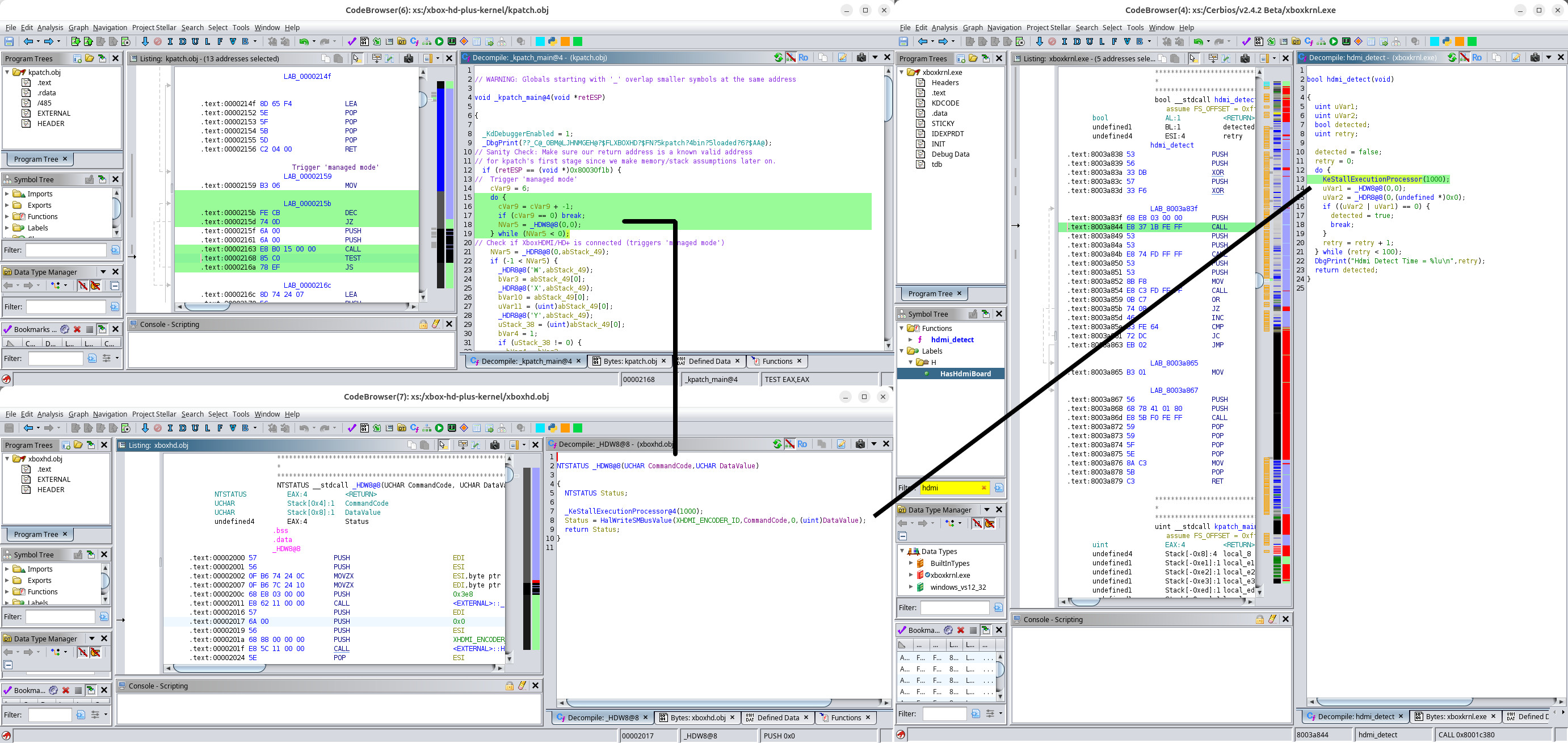

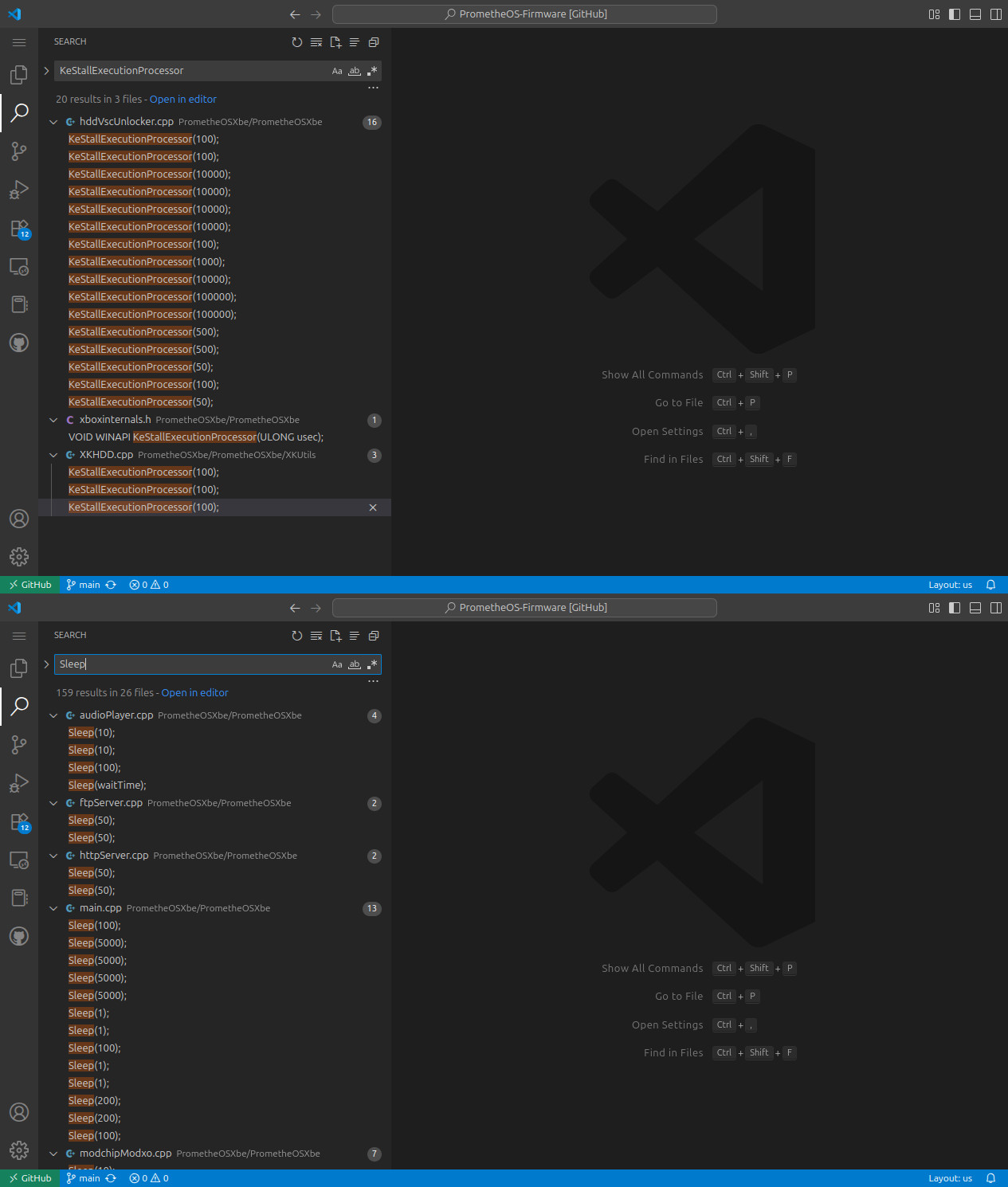

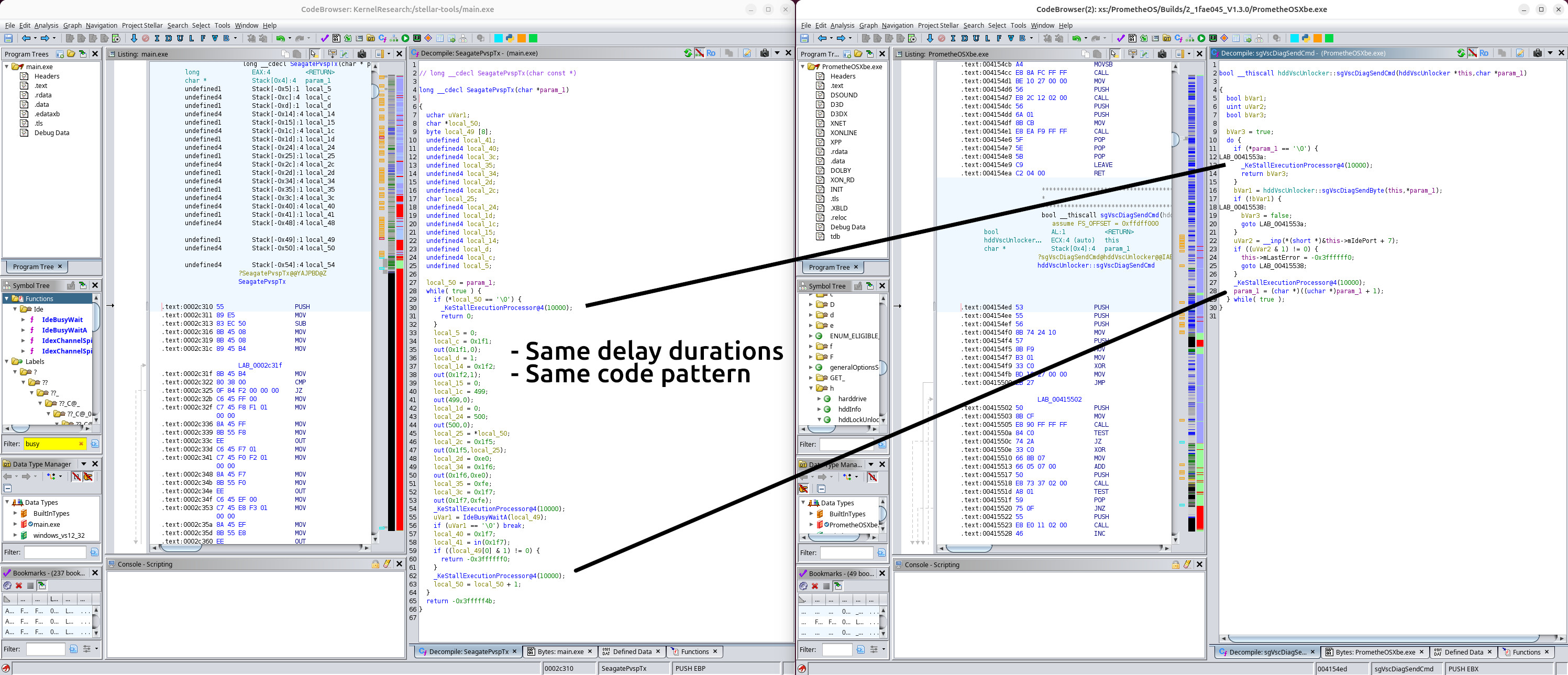

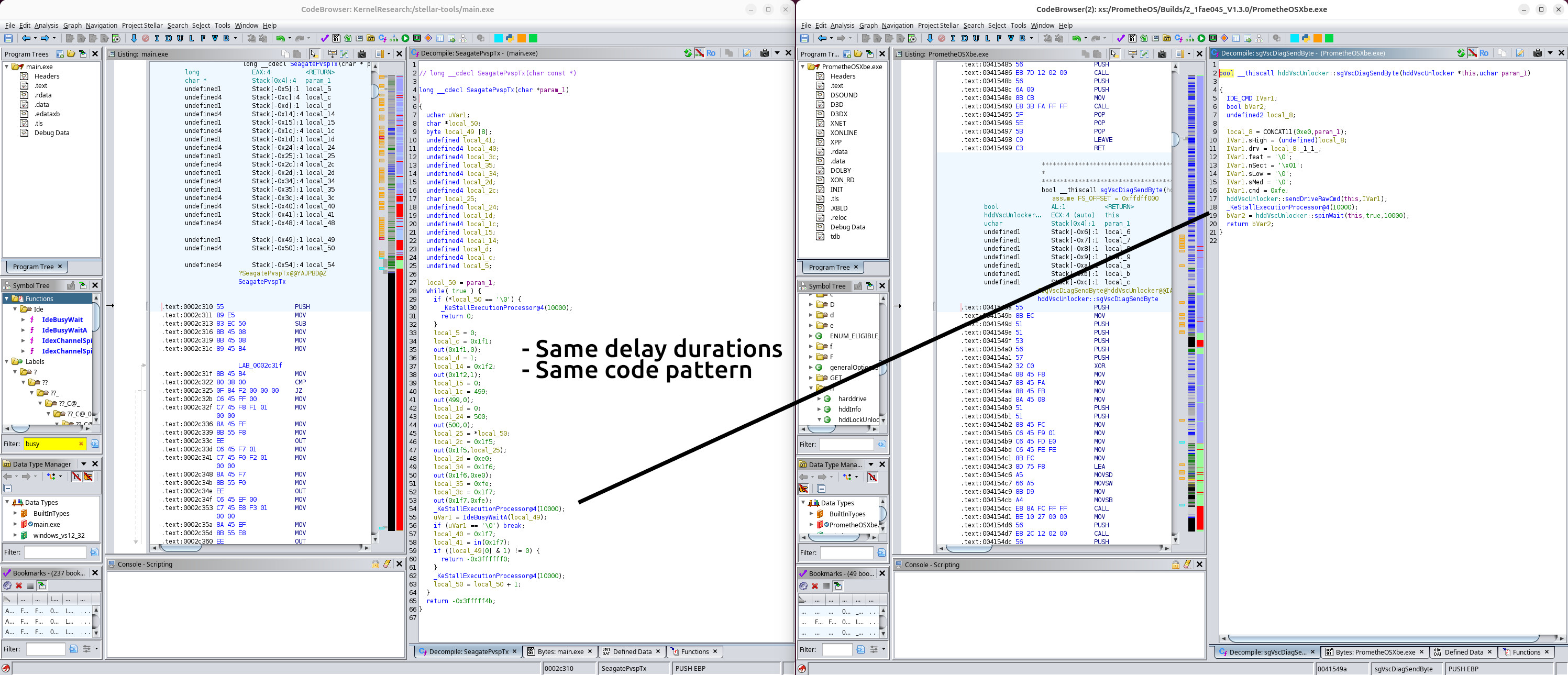

The HDD unlock logic in Stellar was originally written as part of the kernel itself but was moved to an embedded

application (XBE) just before release. Because of this, the core logic remained unchanged. Inside that logic, we rely on

lower-level system functions due to the limitations of the Stellar kernel, which does not include a full runtime library.

Simple functions like Sleep or SleepEx are not available, nor are many standard helper functions. As a result, we used

KeStallExecutionProcessor as a crude but effective way to introduce delays between command sequences.

This approach is completely inconsistent with how PrometheOS typically handles delays. PrometheOS is built using a

stolen version of the official Xbox Development Kit (XDK) and has full access to Sleep, SleepEx, and other XAPI-based

runtime functions. Their codebase contains over 150 references to Sleep-related calls, and only three references to

KeStallExecutionProcessor. All three appear in a legacy method named SendATACommand() that was originally released by

Team Assembly in 2003.

Anyone who has written debug or delay-heavy logic using printf or timing functions knows how unpredictable and arbitrary

these values can be. The same applies here. But now consider this: KeStallExecutionProcessor introduces delays in

microseconds, not milliseconds or seconds. These are one-millionth-of-a-second intervals.

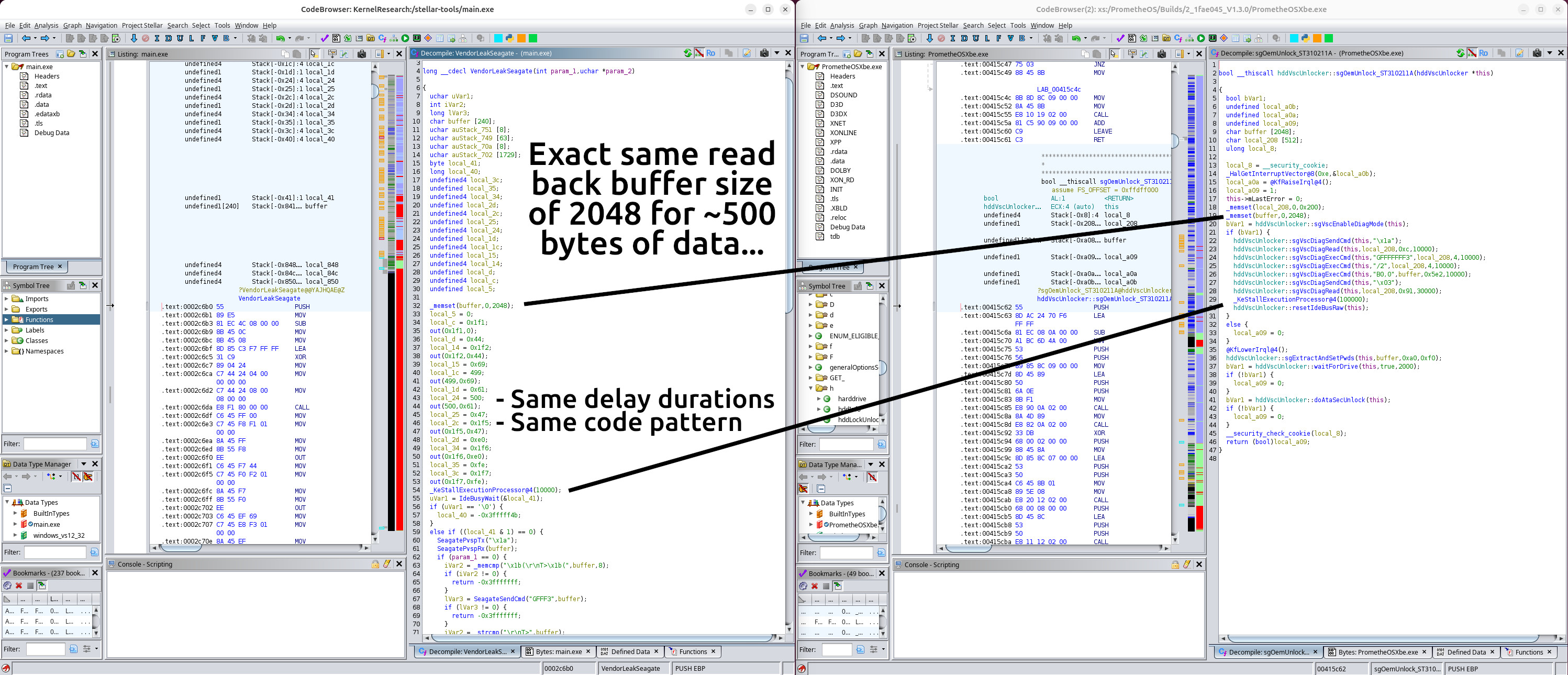

So what are the chances that two completely independent implementations, written by different people in different environments, would not only use the same low-level delay function, but also choose the exact same timing values down to the microsecond?

This comparison of disassembled code represents the bulk of the new HDD unlock logic. It shows a repeated pattern of identical pause logic, matching code structure, and even small but telling details like the use of the same temporary buffer sizes. For example, both implementations allocate a 2048-byte buffer to handle roughly 500 bytes of data. There is no technical justification for that size. It only makes sense if the implementation was copied.

The few differences that do exist appear to be superficial refactoring. In Stellar, we access hardware registers directly through inline instructions. In PrometheOS, these same accesses are routed through member functions. This is another inconsistency that calls the originality of their code into question. Why would you go to the trouble of introducing microsecond-precision delays using KeStallExecutionProcessor, only to throw away that timing accuracy by introducing indirect hardware access? It does not add up unless you consider the possibility that the original logic was copied, then lightly restructured to appear different.

I don’t believe Dream is a developer for PrometheOS when they’re not playing Minecraft. And I don’t believe this code was written independently.

Theft of CPU Upgrade Support

Summary

One of the latest signs of copying appears in CERBIOS’s recent attempt to add support for upgraded CPUs. This is a technically complex area and we are not disclosing any implementation details at this time.

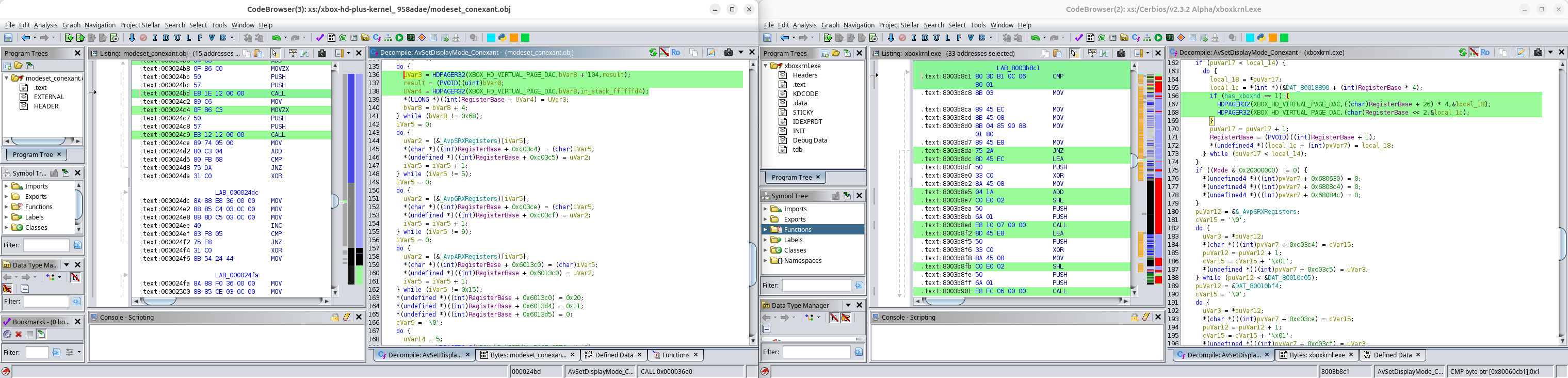

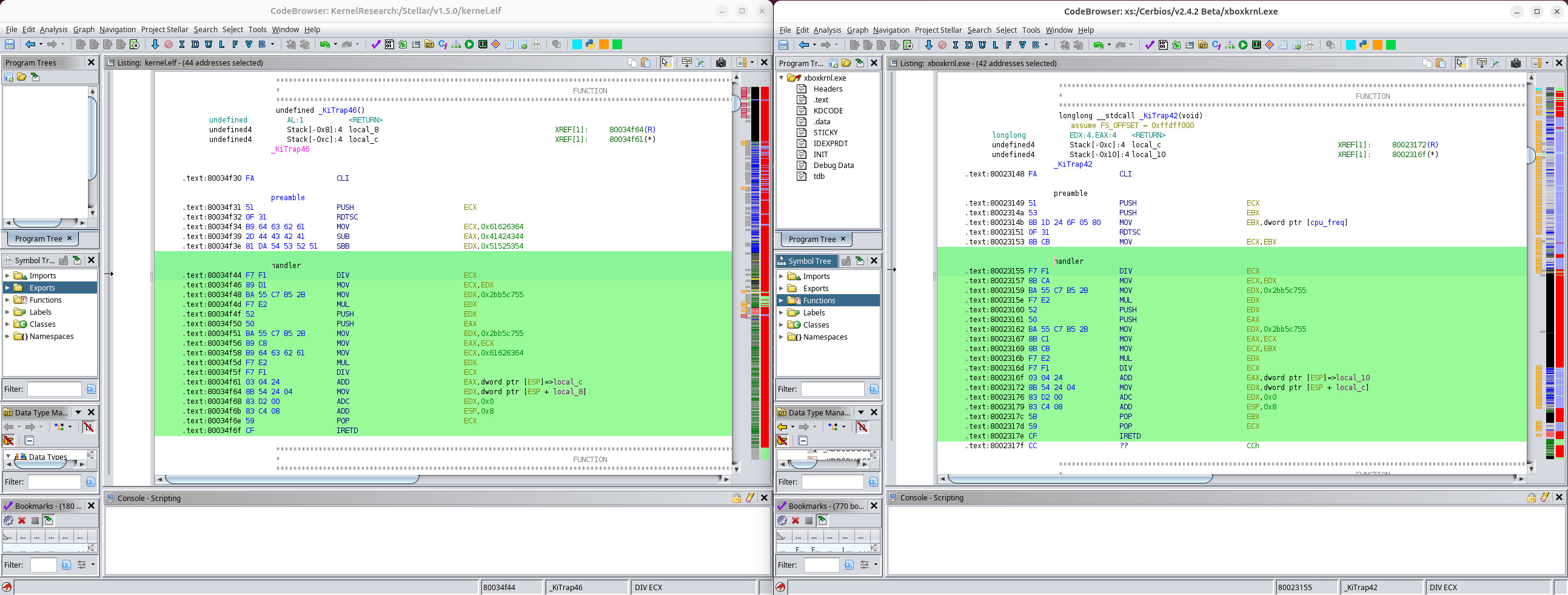

What we can show is a block of handwritten assembly in CERBIOS that matches code found in Stellar with near exact precision. This is not compiled C code or something taken from documentation. This is hand-written assembly, written instruction by instruction, with specific intent. It reflects deliberate choices made during development, not something a compiler would generate on its own.

Side-by-side comparison of handwritten assembly in Stellar and CERBIOS. The instruction sequence is nearly identical. This is not coincidence. This is not reverse engineered. This appears to be copied.

Yet somehow, CERBIOS includes what appears to be the same sequence of instructions, in the same order, performing the same task. These are not high-level abstractions. These are low-level, manual decisions.

It appears that CERBIOS has not yet completed the remaining logic needed to make this functional. But that is not what

matters here. This appears to be yet another case of theft. The code has no reason to exist in this exact form unless it

was copied. The chances of two developers independently writing the same hand-crafted assembly, down to the instruction

and layout, are virtually zero.

Theft of the Xbox Kernel Source Code

Summary

It is no secret that an older, pre-production version of the Xbox kernel source code was leaked years ago. What is also widely known, though rarely acknowledged publicly, is that CERBIOS is that stolen code.

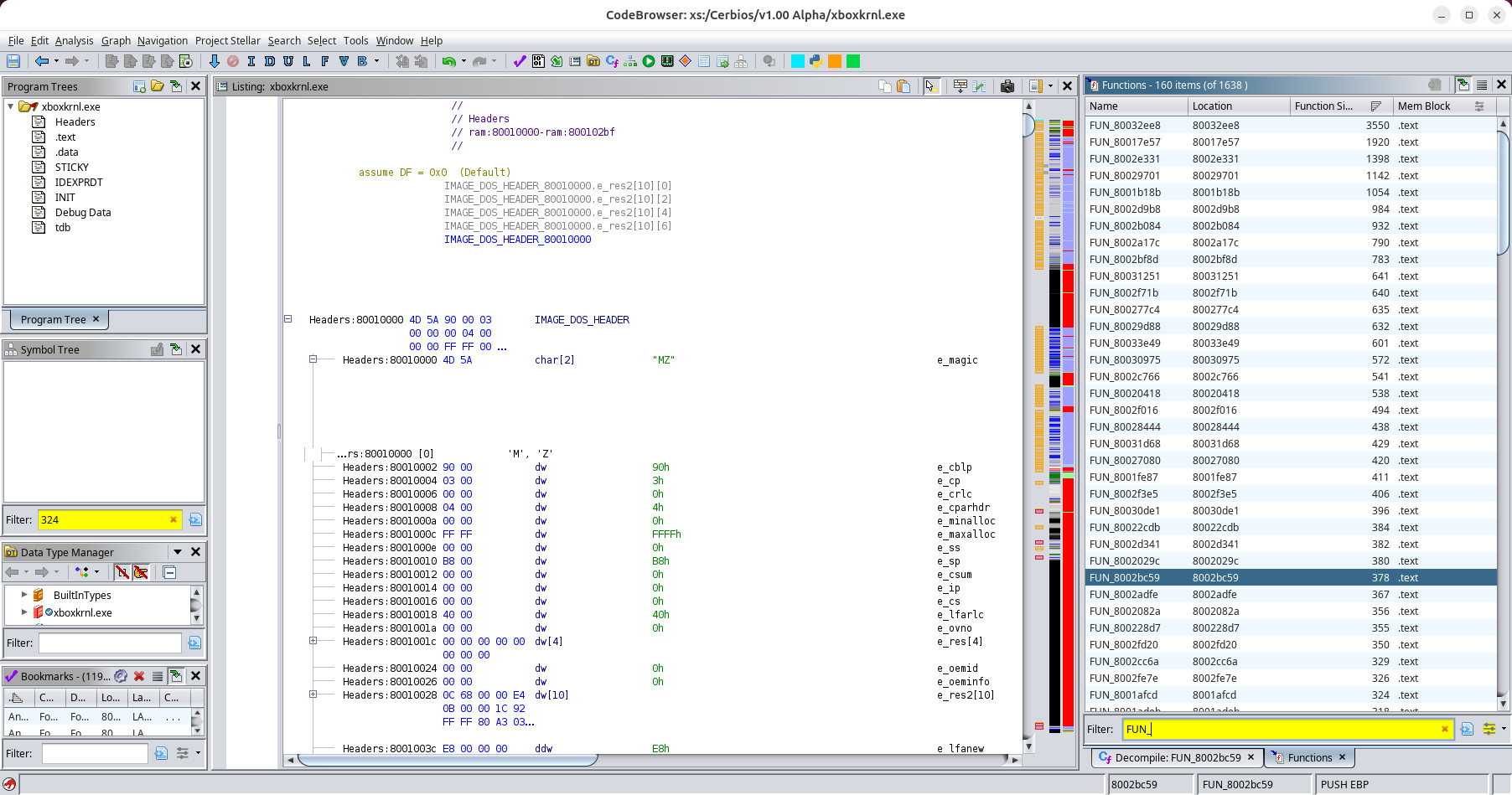

This is not speculation. It is easily verifiable.

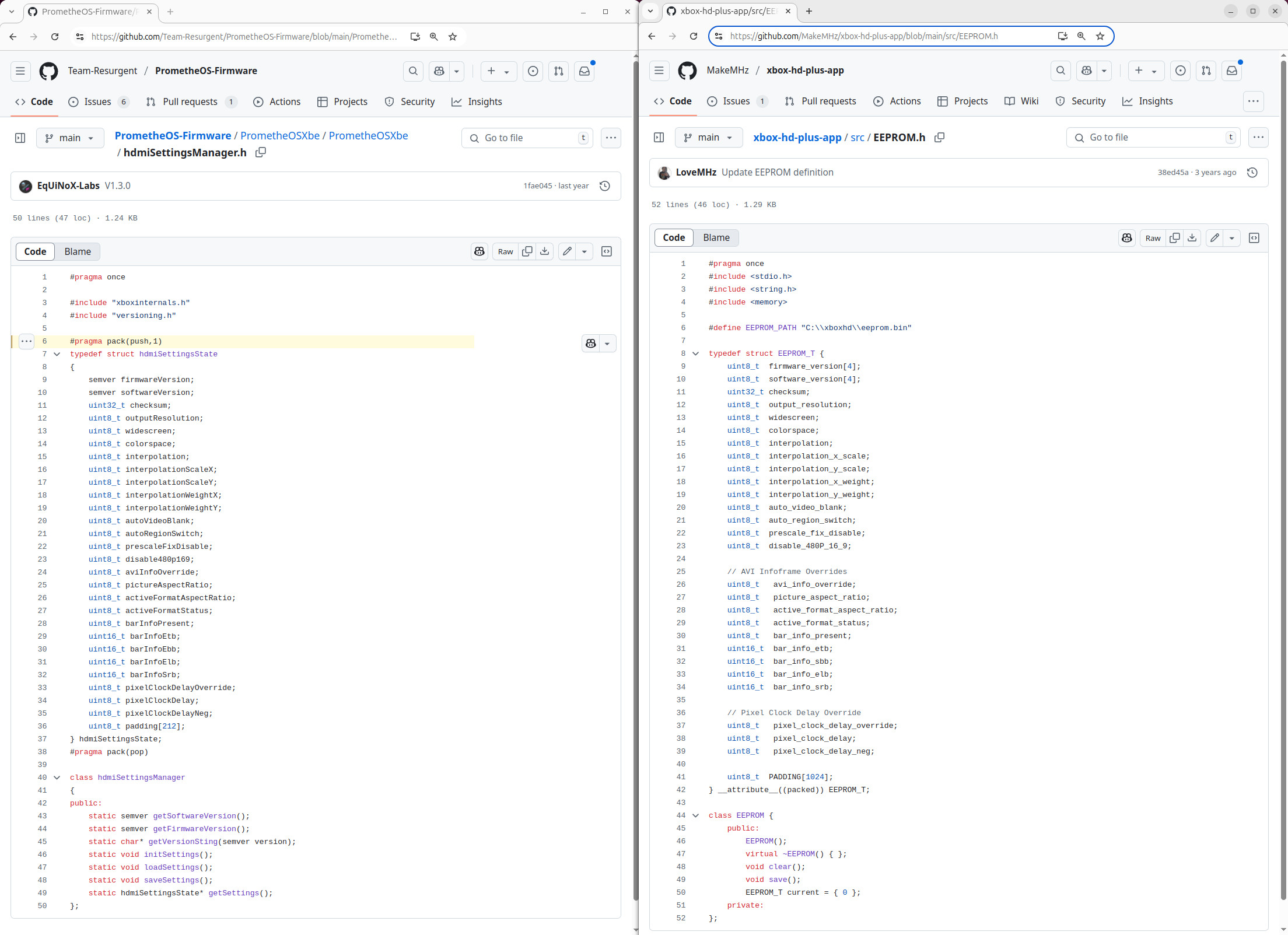

The screenshot below shows how quickly the match can be confirmed. By using symbol signatures from debug and retail kernels prior to version 5000, we were able to identify 1,478 out of 1,638 functions in CERBIOS with no additional effort. Only 160 functions remained unmatched. With a small amount of tuning or adjustments, it would likely be possible to identify nearly 100 percent of the original symbol map.

Out of 1,638 known functions, 1,478 match the Xbox kernel without modification. CERBIOS is not clean-room. This is direct use of stolen Microsoft IP.

This is not a clean-room implementation. This is not reverse engineering. This is just recompiling stolen code.

It is a slap in the face to every developer who has chosen to do the work the right way. Many of us have spent years reverse engineering legal, retail kernels and building our understanding from scratch. That work is slow, difficult, and often thankless. But it is necessary for anyone who respects the boundaries of intellectual property and wants to build something sustainable.

CERBIOS throws that effort away. It relies on a stolen base, masks it with superficial changes, and presents it as

original development. It is not.

Theft of the Xbox Development SDK

Summary

Yet another open secret in the scene is the widespread illegal use of the official Xbox Development SDK. This is not a rare case. It is routine. And it is required to build PrometheOS.

Team Resurgent relies on the stolen SDK as part of their build process. This is not speculation. Their source code contains headers, symbols, and dependencies that come directly from Microsoft’s proprietary SDK. Without it, the project would not compile.

What makes this worse is that there are legal, open-source alternatives available. Toolchains like nxdk have been built from the ground up by developers who respect licensing and legality. Despite this, the team behind PrometheOS continues to take what is not theirs and justify it with silence.

Because the SDK is stolen and unlicensed, no project that depends on it can be considered open source. It does not matter how much code is published. If your toolchain requires pirated software to function, your project is not open. It is not legal. It is not yours.

The use of the stolen SDK is not just a technical shortcut. It is another example of how core parts of these projects are

built on theft. The foundation is illegitimate, and the work that follows carries that forward.

Theft of In-Game Reset Logic

Summary

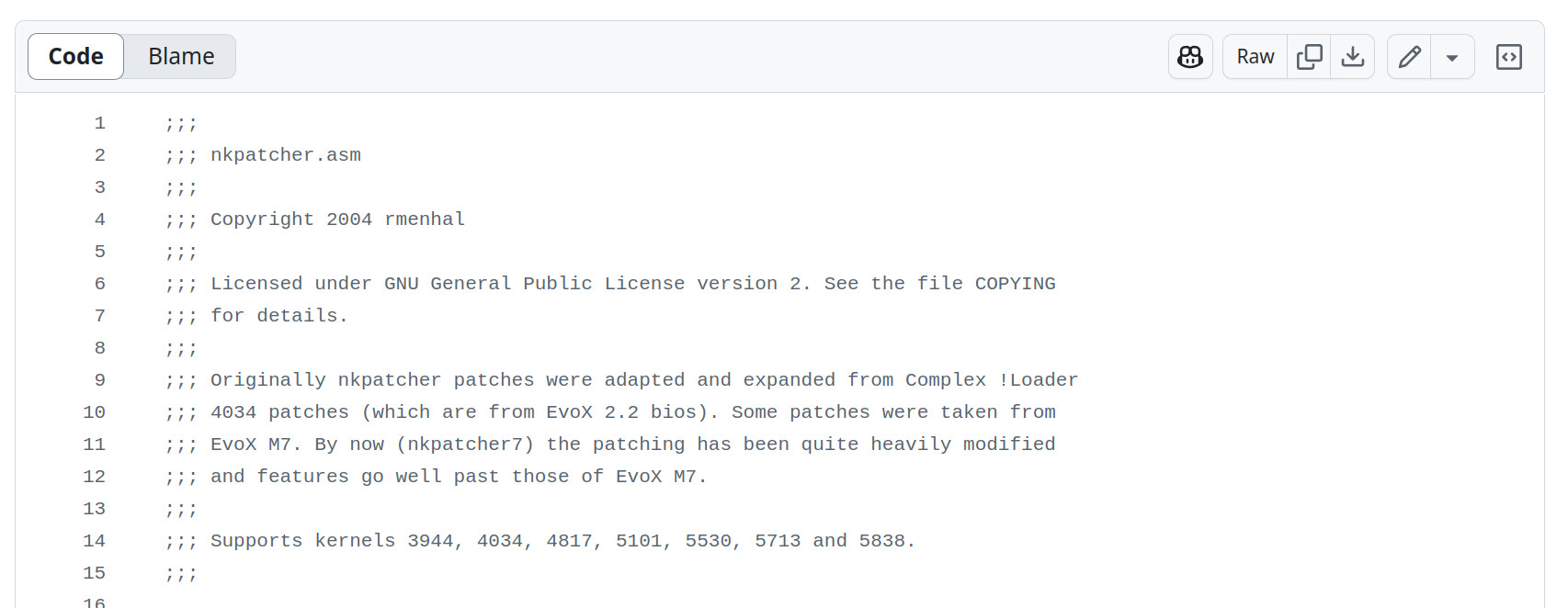

In 2004, rmenhal released an open-source implementation of “In-Game Reset” (IGR) under the GPLv2 license. It is a clever and

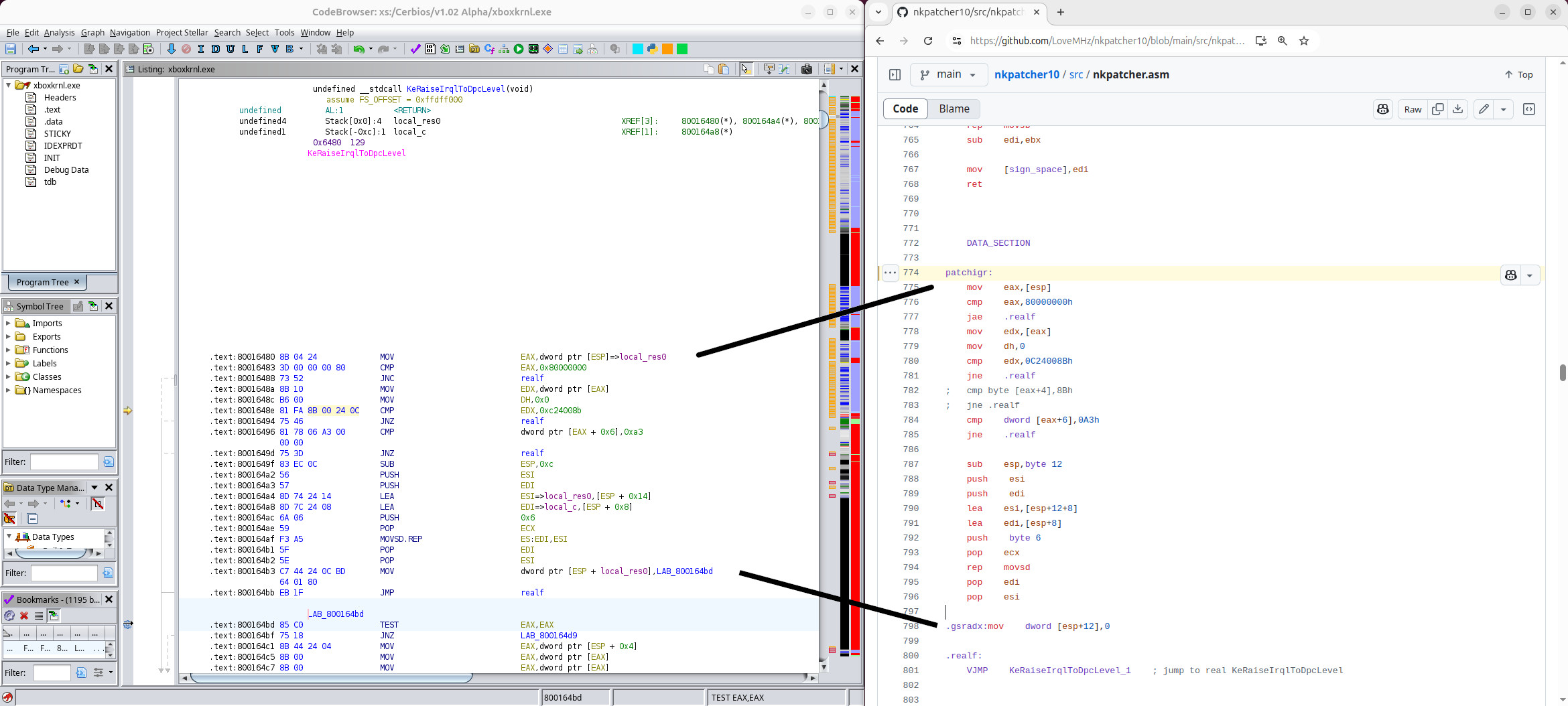

unique approach that works by injecting logic into the KeRaiseIrqlToDpcLevel function. The key idea is to detect if the

function was triggered during the XAPI USB controller input interrupt by inspecting the call stack. Since Xbox applications

embed their own copies of the USB driver, this method allows the kernel to detect controller input with as little of a

memory footprint as possible.

It is a smart solution to a difficult problem, but it comes with a tradeoff: performance. Because this check runs inside

KeRaiseIrqlToDpcLevel, it is triggered on every interrupt raised to DPC level. That adds overhead, especially in systems

that already handle a high number of interrupts.

Project Stellar avoids this entirely. Our implementation of in-game reset does not rely on IRQ-level detection and does

not hook into KeRaiseIrqlToDpcLevel.

CERBIOS, on the other hand, simply copies the original GPL-licensed implementation.

The screenshot above shows the beginning of KeRaiseIrqlToDpcLevel in CERBIOS. The in-game reset logic is clearly visible

and matches exactly to rmenhal’s GPLv2 implementation. It is theft.

This is only a portion of it. There is significantly more IGR-related logic elsewhere in the codebase that is also copied but not shown here.

Other Concerns

There are several additional areas of concern that reflect ongoing issues with code theft, GPL violations, and uncredited reuse. These examples, while not covered in depth above, continue to follow the same pattern of taking work that does not belong to them and presenting it as original.

CERBIOS Virtual DVD (ISO) Support

CERBIOS’s Virtual DVD support behaves identically to rmenhal’s GPL-licensed implementation. Based on decompiled analysis,

it appears they have merged rmenhal’s virtual drive and image-handling logic. This is not a coincidence. The same gameplay

bugs and edge cases present in rmenhal’s code also appear in CERBIOS.

Conclusion

This isn’t the article I wanted to write. But after years of dealing with theft, misinformation, and targeted harassment, it became clear that staying quiet was only helping the people taking advantage of the work we’ve built.

What you’ve read here is just part of a much larger story. For every example shown, there are many more. Every product we release, every line of code, and every idea ends up with someone ready to take it, remove the credit, and pass it off as their own.

But this isn’t just about me. It is about the thousands of people who have supported our work, who expect better from this community, and who believe in doing things right. It is about building a space where legal, creative, and original work can grow without being buried under theft and deception.

If nothing else, I hope this post makes it clear that this behavior is not going unnoticed. It is not acceptable. And it will be called out.

I will keep going. I will keep improving Project Stellar, supporting XboxHD+, and doing the hard work the right way. If you believe in that too, thank you for being here.

This is only part one.